Pitching by the Numbers: Taking a swing at strikeouts

Strikeout rates and swinging strike rates have generally stabilized, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t change. It merely means they are bettable.

But assuming that they are stable can provide some predictive insight into a handful of pitchers who have greatly divergent rates of swinging strikes and strikeouts. It stands to reason that both of these rates should correlate. And since strikeouts are more rare events than swinging strikes, we would reasonably have a bias in favor of the guys who are much better in SS% than K%, and against the pitchers who are significantly lower in SS% than K%.

Looking at our sample of all starters who qualify for the ERA title, meaning they’ve pitched at least one inning per team game, we see that these stats tend to track pretty nicely. The average K% of all these starters is 19.8% and the average swinging strike rate is 21.5%. Pretty close. So we’ll expect SS% to be about 2-3% points ahead of K%. Note these stats are current through Wednesday.

Here’s the full list, but we’ll discuss the pitchers who have a swinging strike rate minus K rate differential that’s about twice the expected average.

We don’t care abut the pitchers whose rate of generating swinging strikes is about average or worse, irrespective of the differential. So that knocks out Gibson, Weaver, Dickey Hudson, Guthrie, Williams and Peralta from the outliers. And it leaves us with Lincecum, Teheran, Richards, Ross, Volquez, McHugh and Nelson as pitchers from whom we would expect significantly more Ks — to a level that’s mixed-league worthy.

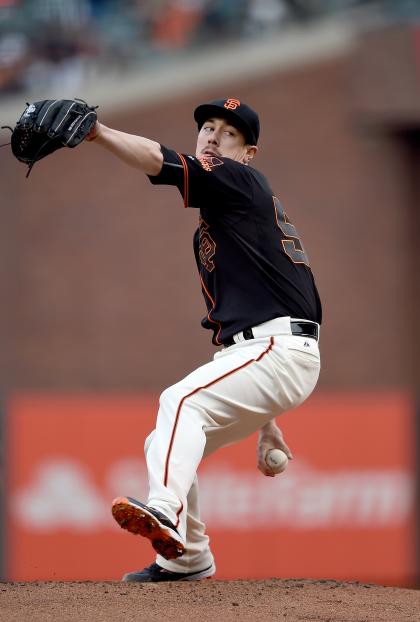

Lincecum is old news. I don’t expect anyone to bet on him at this point without deep reservations. But the other pitchers in the 27 percents have a K% of 24.3%. That would mean that Lincecum would have 58 Ks instead of 45, which is a pretty big deal. Of course that would mean less hits and runs, too. And his ERA is just 3.00 as it is. Do you sense I’m talking myself into Lincecum?

Nelson, similarly, should have more Ks — 67 instead of 60. Basically one more good start. Ross recalculates to about 86 Ks instead of 71 — given that all the other over 30% swinging strike guys have over 30% Ks, too. This would likely transform Ross into one of most valuable fantasy pitchers going forward.

I’m less certain of the degree to which Tehran, Volquez and McHugh are getting shorted as they crowd that 25% group with their sub-par K rates. I can see at some point that small downward movements in swinging strike rates could cause K% to crater but have no idea where that line is. Let’s ballpark them each to being about 5-10 Ks short relative to their swinging strike rates.

At the other end of the spectrum, here are starters who actually have the greatest difference between strikeout rate and swinging strike rate on the minus side — meaning their K rate, somehow, is HIGHER than it should be.

Remember, we said that the average swinging strike rate is about three percentage points higher than the strikeout rate. So a pitcher who has a swinging strike rate more than three points LESS than K-rate is a major outlier. And only three pitchers fall into that bucket: Cole, Colon and Fiers.

I hate saying anything remotely negative about Cole but I must report these findings. We’d all feel a lot better about Cole sustaining that 28% K rate if his swinging strike rate was that high or better. But it’s nearly four points short. The other four pitchers in the 24 percents average a K rate of 23.6%, which would give Cole 12 less Ks (67 instead of his actual 79).

Fiers is a (K-BB)/IP champ but should we believe the Ks? This model says, “No.” He’s earned about 54 Ks, not 69, which would lower his (K-BB)/IP to 0.61 from 0.87 — or to just okay from great.

Guys like Cole, especially, COULD consistently outperform their expected strikeout rate like David Price has done for most of his career. Price is not alone, either. This could be because they are freezing hitters on called strikes. Or it could just be that they save their out pitch for when it’s most able to be leveraged into a K. Or maybe, like a shark, they decide to attack when there is blood (two strikes) in the water.

However, our objective here is to provide models that are simple and lead to simple conclusions. We’re trying to save the time needed to put every pitcher under an analytics microscope because most often these simple explanations — pitchers who have a much higher rate of Ks than swinging strike are lucky in Ks — prove to be the best.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports