Mark Emmert's leadership void marks new normal for NCAA

It’s easy to mock NCAA president Mark Emmert, as his 10-year tenure atop the organization has been defined by inertia, earmarked by apathy and played out to a soundtrack of silence as the organization’s relevancy and popularity has spiraled.

Few moments have underscored the limitations, power hemorrhage and general ambivalence of NCAA leadership more than the COVID-19 pandemic. On Thursday, the NCAA released testing protocol best practices to the membership in concert with the Power Five commissioners. It’s one of the few times Emmert has been publicly relevant during the pandemic since the NCAA shut down the basketball tournaments in March.

As panic creeps into athletic departments and college leaders are engaged in a game of chicken with the pandemic, a consistent question has emerged: “Where’s Mark?”

For so long Emmert has been overpaid and has underproduced that ripping him again would be like pointing out the flaws in the Mike Shula era at Alabama or the pitfalls of the Herschel Walker trade. Emmert’s pandemic paralysis is actually instructive to the future of college sports, as it underscores how powerless the job of NCAA president is currently and will be moving forward.

“I think it becomes a little bit more of a figurehead job,” said longtime athletic director Jim Livengood, who is a consultant with Vivature out of Dallas.

The Power Five commissioners, who actually run college athletics, have long vacuumed the power out of Emmert’s office, as their influence has spiked the past 15 years with the financial dominance of football. The NCAA doesn’t oversee the College Football Playoff, and that leads directly to the void of any juice.

As those trends have been established, Emmert has receded into the background. More telling than his lack of popularity is the general sentiment that he’s not trying. It would be stunning if more than 15 percent of athletic directors approved of his performance. (One pointed out that Emmert did become more engaged when Congress undressed the NCAA for a lack of a cohesive COVID-19 policy in early July.)

Emmert has wisely bonded with the NCAA presidents — his former colleagues from his time at Washington and LSU who sign his paycheck and have allowed him to survive and advance.

With the salary that Emmert is pulling in — $2.7 million in the latest available filings, but as much as $3.9 million in recent years — it’d be naïve to think that the gig won’t be in demand when his reign of apathy finally ends. And it’d also be crazy to think that Emmert would leave before his deal ends in 2023 (with an option for 2024), as the gig has evolved to the administrative equivalent of a blue-chip recruit making $10,000 to mow a booster’s lawn.

But the role of NCAA president has been neutered. The rise of football and the NCAA’s lack of control over it has left the NCAA president as a ceremonial position.

“College football is the driving power for college athletics programs,” Livengood said. “It’s been that way for quite some time. Football has grown so big, that’s the dynamic. And I don’t know how a shift can be made.”

The lack of NCAA leadership in the pandemic has again led to calls for a commissioner in college football. On Thursday, it was UNC coach Mack Brown calling for one on “The Paul Finebaum Show.” (Mike Krzyzewski has long called for one of these in basketball.)

But when the czar idea for college football is tested around college athletics, it’s greeted with chuckles among the sport’s leaders. It makes for an easy column and bar argument.

Here’s the reality: Would the Power Five commissioners really cede power to one individual? For an answer, simply ask why the Rose Bowl and Sugar Bowl have the best time slots available in the sport instead of the College Football Playoff semifinals. The lack of centralized leadership has led to refined greed and territorialism among the individual conferences, who have long defiantly clung to their piece of the cookie over the greater good of the sport.

That’s why a confounding void exists.

“Who is looking out for the good of college football, that’s the million-dollar question?” said veteran Louisiana Tech coach Skip Holtz. “Because of the direction, there’s not anyone centralized. There’s no one pointing everyone the same way. For the longest time, the NCAA was that governing body.”

Remember the day basketball conference tournaments shut down for good back on March 12? There was the Big East awkwardly playing on at Madison Square Garden while the dominoes of other leagues canceled their tournaments. It made mosquito herding look organized, as there was no centralized leadership. The upcoming weeks and months with college football are all just exaggerated versions of that.

“I think it’s communication,” said Tulane athletic director Troy Dannen about a lack of centralized leadership. “Who is making the decisions and what’s the thought process behind any decisions? Everyone is making decisions that seem to be in the conference’s best interest. This is the one sport where decisions aren’t made in the interest of the membership as a whole. That’s the governance model, that’s not Mark Emmert or anyone else’s fault. That’s the way the governance model has evolved.”

The pandemic offered a time for Emmert to show leadership, collaboration and vision. But he’s remained largely hidden, with officials around the sport noting that the role of NCAA chief medical officer Brian Hainline being one of the few useful things the organization has offered during the pandemic.

Instead of showing significant leadership in March, Emmert infuriated leaders around college sports with the lack of communication on the eventual NCAA tournament decision and the cancellation of spring sports.

The most vitriol toward Emmert these days comes from the NCAA’s bungling of Name, Image and Likeness. Instead of showing the vision and aggression to lay out a national policy that could have defined his tenure, the rules are now being dictated by local legislation and political grandstanding.

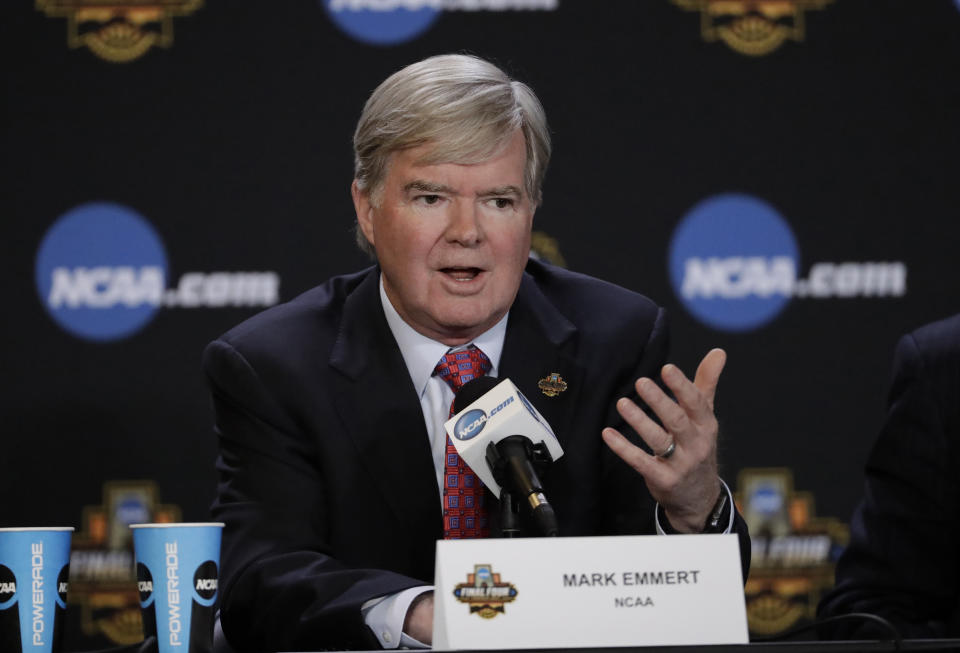

Since the overreach on Penn State in 2014, Emmert has shown limited ambition and flashed little public presence. His affinity for misspeaking has even got him flanked by NCAA presidents at Final Four press conferences to deflect the difficult questions.

Early on in Emmert’s tenure, he was filled with bold talk, energy and ambition. But after he failed to earn enough votes to get a $2,000 stipend shepherded through early in his tenure in 2011, he realized the complications inherent to NCAA leadership.

Much of his drive appeared to dwindle from there.

“I don’t feel impotent, or I wouldn’t have taken the job,” Emmert said back in 2010. “I’m not interested in just going around and making speeches.”

Instead, he’s treaded water and cashed checks for a decade. There’s no better way to summarize Mark Emmert’s career than the silence on the other end of the phone when you ask an athletic administrator a simple question: “What is the most significant thing Mark Emmert has done in 10 years?”

It’s the same answer to what significant leadership he’s illustrated during the pandemic. And why his legacy on the president’s position will be that the only thing he managed to improve has been the job’s earning power.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports