NBA players’ union leader takes bold stand

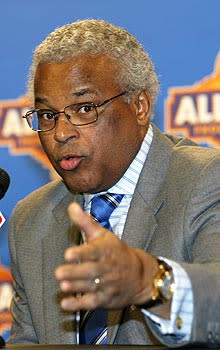

NEW YORK – Across the Staples Center locker room, the NBA’s All-Stars waited for commissioner David Stern and Players Association executive director Billy Hunter to deliver the perfunctory rah-rah remarks they regurgitate every year on the eve of the game. Only, Hunter had a different plan, unleashing an inspired soliloquy to frame the gathering storm of labor strife. And it may have just transformed the way the biggest stars in the sport see him.

The room was thick with league executives, coaches and players on the afternoon of Feb. 19, and they listened to Hunter insist he couldn’t come in good faith and tell them everything was well within the NBA. Hunter said the owners had made a crippling proposal, a long lockout loomed and these players in the room would bear the biggest financial and public relations burden of a work stoppage. And then he started to tell them he had thought long and hard about the way Oscar Robertson and Jerry West staged a protest at the 1964 All-Star Game, threatening a boycott until they had leveraged the league into the most rudimentary of medical benefits and pension contributions.

Yes, Hunter had been thinking long and hard, losing sleep over the possibility of declaring an uprising of his own. He dropped dramatic, long pauses and left everyone – including Stern, who had started barking into the ear of his deputy, Adam Silver – thinking that Hunter had come to advocate the players make some kind of bold stand themselves in Los Angeles. In the end, Hunter stopped short, insisting the All-Stars had an obligation to play the game, but the message to the players was unmistakable: Hunter wouldn’t back down to Stern, and maybe even had the ability to rattle him, the way the commissioner and owners had been trying to unnerve the players.

So livid, Stern would barely even look at Hunter when Hunter handed him the microphone. And soon, Stern started reciting his résumé, his decades of labor fights and legal battles in the NBA. Here’s how much the NBA was worth and here’s where I’ve brought it, he said. Everyone could see the anger rising within him, but no one expected the words that tumbled out of his mouth.

Stern told the room he knows where “the bodies are buried” in the NBA, witnesses recounted, because he had buried some of them himself.

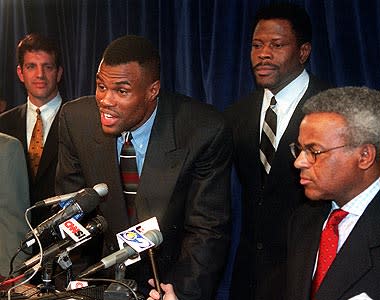

“It was shocking,” Chicago Bulls star Derrick Rose(notes) told Yahoo! Sports. “I was taking off my gear, and when he said that, I just stopped and thought, ‘Whoa …’

“I couldn’t believe that he said it.”

Rose wasn’t alone. Said another All-Star in the room, “I was shocked … just shocked.”

Whatever implications were intended with Stern’s words, several players declared the scene to be a galvanizing moment. It was “probably the best Billy has been around us,” one veteran Eastern Conference All-Star told Yahoo! Sports. Out of fear of league retribution, several witnesses in the room didn’t want comments attributed to them.

The prospect of a lockout cutting into next season is frightening for everyone, and it wasn’t enough for the players to simply listen to Hunter tell them to prepare for a year-long work stoppage, to understand the issues separating the sides. The players needed to see Hunter get in a room with the commissioner, push back on Stern and his billionaire owners. They’ve always seen Stern so cool, so composed, so prepared for everything with a calculated, deft answer, but now they had also seen him riled. They had seen the simmering of his infamous temper. For all the talk of the players’ disjointed ranks, Hunter had gone a long way toward cementing the support of his most important constituents.

“Especially Billy talking like that with David in the room, it makes you feel good,” Rose said.

Hunter is standing between the players getting their contracts rolled back and the league implementing a hard salary cap. The NBA’s players have watched the NFL players union decertify and go to federal court. They understand that football's ruling will shape the forever of pro basketball.

“Every basketball player knows about the NFL – and that’s always been their biggest dread and concern,” Hunter told Yahoo! Sports in an interview at his office recently. “The boogeyman is the system that the players play under in the NFL.

“Ironically, a lot of the same things that David and the owners are demanding now are identical to what they were demanding in ’98. He said, ‘I think every one of my owners should have a guaranteed $10 million profit per year. I said, ‘Bull… . ‘What they have is predicated on how they manage their teams. Nobody forces them to sign anyone.

“It’s the same argument: ‘We’ve got these guys who got six-year deals and I’ve got to pay this guy …’ Well, [expletive] it. Why did you give it to him? Nobody put a gun to your head.”

This could be the final fight for Billy Hunter, and this time he sounds like he wants to take on everyone. This is a propaganda machine within the NBA, a world where everyone is on the payroll – or wants to be on it. From television partners to the biggest names in the sport’s history, Hunter has to make a case for a union that’s mostly composed of young, rich African-American men. As for the PR war, Hunter confesses, “We can’t win it.”

The public will forever believe the players are overpaid, that the system tilts against the owners, no matter how the facts play out. Still, Hunter sounds unwilling to sit back and let Stern and the owners dictate the terms of engagement. That’s how it’s always gone, but Hunter sounds willing to treat Stern’s surrogates like the commissioner himself: as an enemy of the players association.

The NBA employs so many former stars like Julius Erving, using them as glad-handers who tsk-tsk on today’s players. “Most people may not realize that Dr. J works for the league, that they parade him around the country,” Hunter says. “They should’ve asked Dr. J for his income tax statements, and see how much he got from the NBA last year.”

The league “has got to play hardball,” Julius Erving told ESPN.com at ESPN the Weekend in Orlando. “When I played, the owners had the power. The prisoners are running the prison now, not the warden. The warden is strong and he has say-so but, the balance of power is definitely with the players.”

Nevertheless, this is still Hunter vs. Stern II. They pushed the NBA season to the brink in ’98, and feel like they’re headed there again. Only this time, Stern’s world has changed. The owners are younger, brasher and bought into the NBA at far steeper prices. Once, the owners allowed Stern to set the agenda. That isn’t always true anymore.

“I don’t think he has the sway that he once did,” Hunter said. “I’m not saying that he’s not the commissioner and does not have the power to act. But I don’t know that he has the unfettered, undying support that he had before. There’s maybe a little crack in the dike.”

This time, Hunter has gone deeper to solidify his own ranks. For two years, he’s traveled the league, meeting with players and imploring them to save money for a lockout. Over All-Star weekend, he spoke to the players’ mothers at a luncheon. And he did something else he had never done before: He gathered the players’ business managers, entourages and hangers-on for a meeting. This wasn’t popular with the players’ agents, but there’s long been something of a gulf between Hunter and them.

“Some of the agents are pissed because they say that I ended up legitimizing the [entourages],” Hunter says.

Many of the most powerful agents still believe Hunter doesn’t include them enough in the decision-making process, that he should consult them more in the fight with the league. So many of them are more comfortable dealing with the union’s top attorney, Ron Klempner, but feel like Hunter is too inaccessible to them. They’ve all met with him in recent months, but they want a greater role that he’s reluctant to give them.

“My door is open,” Hunter said, “but am I going to run it by some agents every time I make a decision? That’s not happening. When I came in ’98, for the most part, the agents ran the union. I had to wrest control from the agents.”

In this information age, it’s far easier for Hunter to deliver information to his players, but rallying them is something else. That’s harder, and that’s ultimately the most important element of this labor fight. The commissioner and owners are banking that the players won’t get too far into a lockout because they won’t want to live without the paychecks, that they’ll cave to the hard-line owners demanding historic givebacks.

This is the reason the scene in the locker room was so important, because the players needed to see Hunter unafraid of Stern, unafraid of taking the fight to him. It is rare that the players get to see the two go one-on-one, because the commissioner and owners have been so uneasy with negotiating sessions that involve the league’s elite stars.

This year, Hunter said he told Stern this story: “I don’t know where you were raised, but I lived with rats. I used to kill rats. We had a .22 rifle and we would lay in the kitchen and shoot them on the floor. One thing my grandmother taught me was that if you got a rat trapped, you’ve got to give his ass a way out, because he will fight you if he has to.

“If you don’t give us a way out, a chance for a compromise, you’re going to get a fight.”

After the players watched David Stern drop the line about bodies buried in the NBA and march out of that Staples Center locker room, his entourage of suits and yes-men falling into formation behind him, they smiled and nodded, thrilled that Billy Hunter had thrown him off balance. The NBA’s players needed to see it in February and they’ll need to see it again and again. The fight’s on.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports