Should we be worried about monkeypox in South Florida? Here’s what you need to know

Monkeypox is on your mind. How can it not be?

For more than two years, we’ve lived with contagious COVID-19 and still have to take precautions as new variants arise.

Now, the world health community is talking about something else that is contagious, monkeypox, and it has caught the attention of the Biden administration and local health officials — including Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava and the Florida Health Department in Broward.

That’s because there are two confirmed cases in Florida, according to Broward’s health department. One person’s illness is related to travel, the second person did not travel and caught it in the United States, said Dr. Aileen Marty, a Florida International University distinguished professor in infectious diseases and director of the FIU Health Travel Medicine Program and Vaccine Clinic commander.

Following news that 2 presumptive monkeypox cases were identified in Broward, Miami-Dade is monitoring the situation & my team was briefed by@JacksonHealth.

The bottom line: It's not novel and exposure risk remains low. Educate yourself on the symptoms: https://t.co/cbfSDaJywL— Daniella Levine Cava (@MayorDaniella) May 23, 2022

You have questions. So the Miami Herald spoke with Dr. Marty to answer some of the most pressing things you need to know — including how to avoid catching the virus.

What is the monkeypox virus?

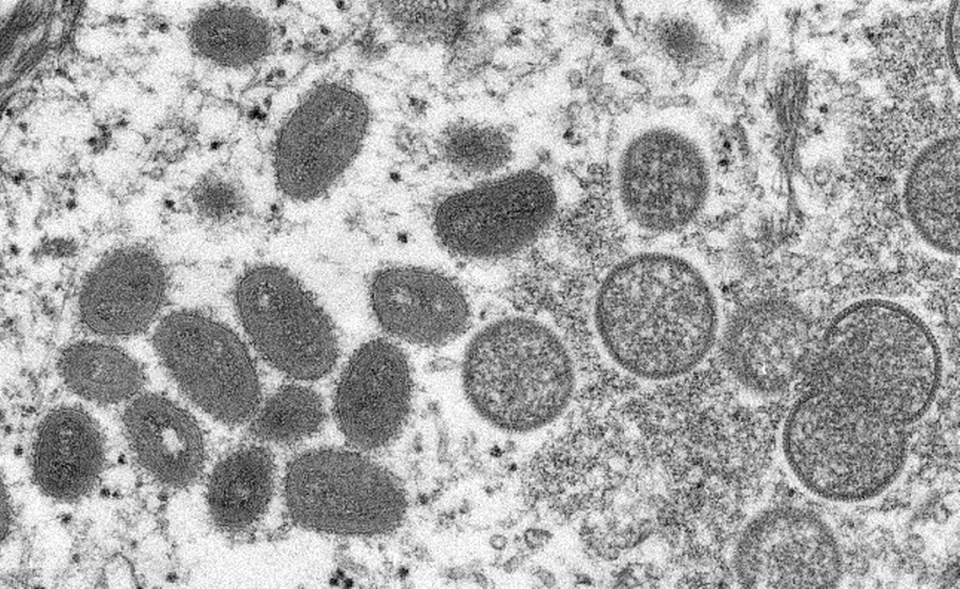

Monkeypox is a rare disease that was first discovered in 1958 when two outbreaks of a pox-like disease occurred in colonies of monkeys kept for research, hence the name, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since then, monkeypox has been reported in humans in other central and western African countries.

On May 18, a U.S. resident tested positive for monkeypox after returning to Massachusetts from Canada. Then two more cases were reported in South Florida. Europe has also seen some activity in May.

FIU’s Dr. Marty adds detail: “The monkeypox virus is a true pox virus (orthopox), just like the variola virus that caused smallpox. Orthopox viruses are DNA viruses — very different from flu or SARS-CoV-2, which are RNA viruses. Nearly all documented human cases — since it was first described to cause human disease in 1970 — have been transmitted from an animal to a human. Animal-to-human transmission is usually via a bite or scratch, preparation of wild game, and direct or indirect contact with body fluids or lesion material.”

How is monkeypox spread from one person to another?

“Uncommonly, human-to-human spread can happen, and when it does, the monkeypox virus spreads via bodily fluids, including respiratory droplets and genital secretions,” said Marty.

“Historically, human-to-human spread has happened among family members or individuals in congregate settings — [such as] prisons. But this time it is happening mainly from a different close encounter, the sexual encounter,” she noted.

“Currently, the CDC is distinguishing persons with direct contact — exposure to the skin, crusts, bodily fluids, or other materials — as high risk and those with indirect contact — presence within a six-foot radius in the absence of an N95 or filtering respirator for three or more hours — with a patient with monkeypox as lower risk. But health departments should monitor even those people.”

What are monkeypox symptoms?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, symptoms of monkeypox include fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, chills, exhaustion and swollen lymph nodes followed by a rash.

The distinctive clinical features of monkeypox happen after the first symptoms, Marty adds. After an incubation period of five to 21 days, but usually six to 12 days, infected people get early symptoms like a bad headache, fever, back pain, muscle ache and swollen lymph nodes.

These early symptoms generally last one to three days and then comes the rash.

“The rash is unusual because it classically starts on the face and the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, followed by rash elsewhere — but in the current outbreak, that has not been the usual spread. In this outbreak, lesions have manifested first in the groin, and the prodrome [early symptom] has not been as severe or notable,” Marty said.

“Curiously, experimental infections in monkeys also show genital lesions,” Marty said. “Genital lesions could easily be mistaken for a different infection by someone unfamiliar with monkeypox manifestations.”

READ MORE: First US monkeypox case reported this year, health officials say. What to know

When are people infectious?

People are infectious from a few hours before the first symptom manifests until the scabs are dry and gone.

According to the CDC, lesions progress through the following stages before falling off: macules (flat lesions), papules (well-definined skin bump), vesicles (blister, filled with clear fluid, usually), pustules (bulging fluid containing pus) and scabs.

The illness typically lasts for two to four weeks. “In Africa, monkeypox has been shown to cause death in as many as one in 10 persons who contract the disease,” the CDC said.

The rash is typically painful, Marty adds, and the scabs contain infectious viral particles.

Is the Miami area more likely for a spread of monkeypox because of international travel?

Travel isn’t the only way one can catch monkeypox.

“We have a high incidence of sexually transmitted infections in Miami-Dade and sexual transmission is currently the dominant transmission in this outbreak. Thus, the combination of behavior and international travel poses an increased risk for our community,” Marty said.

Is this outbreak of monkeypox a challenge to public health?

A healthcare adviser with the World Health Organization recently told the Associated Press the current and “unprecedented” outbreak of monkeypox in developed countries appears to have been caused by sexual activity at two recent raves in Europe, in Spain and Belgium.

“But anyone can be infected through close contact with a sick person, their clothing or bed sheets,” the AP reported.

“This new outbreak that is primarily spreading in the gay, bisexual and men-who-have-sex-with-men community produces new logistic and public health challenges,” said Marty. “The long incubation period is also part of the challenge because people can be infected for almost three weeks before showing any disease.”

Treatment for monkeypox?

“There is no specific antiviral treatment for monkeypox, but the virus has many similarities to the variola virus of smallpox, so the antivirals developed for smallpox will help people with monkeypox,” Marty said.

If you suspect you may have monkeypox or been exposed to it or it’s been confirmed you need to seek immediate medical attention. This can not only help you but it can help others.

“Monkeypox is a reemerging infection with an unusually high spread, unpleasant at best and deadly at worst — though death is very unlikely and has not yet been seen in this outbreak,” Marty said. Monkeypox can produce scarring and serious consequences if the scarring involves a vital organ, like the eyes.

There is a newly approved antiviral, tecovirimat (ST-246), but it is not widely available, according to Marty. If a person is not yet symptomatic, there are vaccines that could prevent severe symptoms. The CDC is asking physicians to use cidofovir or vaccinia immune globulin to control monkeypox.

“Similarly, the new Jynneos vaccine is not widely available, nor is the old ACAM2000, but working with the Florida Department of Health, physicians may be able to obtain these newer solutions,” Marty said.

Will my decades-old smallpox shot help?

Those of us of a certain age may recall getting the smallpox vaccination. That’s the one that left a dime-sized scar on our upper left arms, according to WebMD. But routine vaccination against smallpox, which was largely wiped out by the worldwide vaccination program that began in 1958, largely ended in the United States in 1972.

Post-9/11, there was some movement in the early 2000s to revive the smallpox vaccination program for healthcare workers should there be a bioterrorist attack using smallpox as a weapon, the New York Health Department noted.

Will that scar pay off with immunity for the 50 and over set?

Somewhat, Marty believes. Accent on the somewhat. “Persons who got a smallpox vaccine over 50 years ago have minimal T-cell memory from that vaccine but virtually no neutralizing antibodies,” she said.

What can you do to protect yourself now?

We know what to do to protect ourselves against COVID-19 — take the vaccines and boosters, wear a mask, practice social distancing. We’ve heard the drill even though some refuse to heed health experts’ advice.

But what about monkeypox?

“From an individual perspective, situational awareness and standard public health measures will reduce the risk, including hygiene and asking questions before engaging in sexual relationships, Marty said. “Because transmission via respiratory droplets is a risk, masking is critical for healthcare workers, and in particular for healthcare workers and other employees at sexually transmitted infections clinics.

Who is at the most risk?

Currently, the most likely to get infected are sexually active individuals, particularly those in the gay, bisexual or men-who-have-sex-with-men community and healthcare workers who encounter infected persons, according to Marty.

“But the risk of severe disease is highest for children, pregnant women and those with severe underlying conditions.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports