Mom raises red flag over staff shortage at Kingston hospital

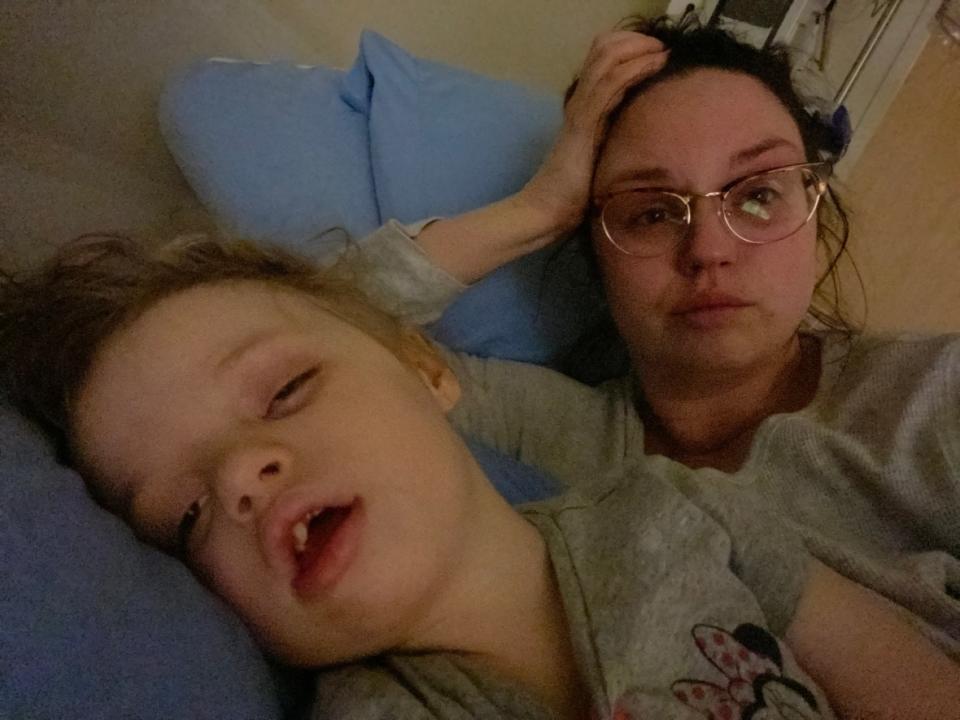

After months of frequenting the Kingston General Hospital, one mother says she's concerned about a staff shortage at the hospital's pediatric critical care unit after having to take on nursing duties for her sick child.

Vanessa Ivimey's daughter Ivy Murray has a gene mutation called SCN2A, known to cause early-onset epilepsy and developmental delays.

The three year old's symptoms include seizures, which Ivimey said intensified in April of this year after the family tested positive for COVID-19.

The two have spent more than 40 nights in the hospital between April and July, and Ivimey said she's witnessed a disturbing staff shortage in that time.

"I see nurses having to make decisions over what child to take care of first," she said, adding that most days she counted four nurses to cover both the regular in-patient pediatric unit and the critical care unit.

"It's definitely never a bountiful amount of staff where you feel like … they're adequately able to help you and your child."

WATCH | Parent raises alarm over staff shortages in pediatric unit at Kingston General Hospital

Losing trust in medical system

Ivimey said the lack of nursing staff forced her to take her daughter's care into her own hands.

After noticing her daughter wasn't receiving necessary medications on time, Ivimey said she started bringing medication from home.

She also decided to learn how to use the oxygen machine her daughter sometimes needed during seizures.

In one instance, she said she buzzed for help and her daughter "was turning blue."

"Nobody was coming … so I ran back into our room and I did what I saw the other nurses do. I put her on her side, I turned the oxygen machine on. I put the mask over her face. I made sure she was breathing properly," she said.

Ivimey doesn't blame the hospital staff or nurses for these incidents, but rather the medical system as a whole.

"To think that the children's unit is unworthy of the same care that the other units are getting, it's really hard to not get angry," she said, adding that she feels compassion for overworked staff.

The experience has taken a toll on Ivimey's mental health, and she said that makes it challenging to focus on her daughter's care.

Hospitals in critical staffing shortages

The Kingston Health Sciences Centre said the hospital is one of many across the country facing critical staffing shortages in all units and programs, including pediatrics.

"This shortage is the result of a number of factors," the hospital said in statement, listing absences, early retirements, and staff leaving the health-care industry as some reasons.

While the health centre is actively recruiting to fill vacancies, a lack of trained health-care providers across the province has made it difficult.

The hospital suggests anyone with concerns to contact its patient relations team.

Ivimey said she hasn't done that because she's worried her concerns will be misunderstood.

"They have phenomenal nurses and a social worker, and admin staff that are there that are trying really hard, and I'm always concerned that it's going to come across like I'm saying the staff aren't doing their jobs," she said.

"That's not the case."

Do something now, union says to province

Doris Grinspun, CEO of the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO), said Ontario was already short 22,000 registered nurses before the pandemic began and the shortage has only gotten worse, subjecting nurses to higher workloads to make up for the deficit.

"Unless something is done substantively very, very soon, there might be a place of no return," she said.

A few months from now it may be too late. - Doris Grinspun, RNAO CEO

Grinspun said a survey conducted by the RNAO indicates that 75 per cent of nurses are burnt out while more than half are considering moving away from patient care or leaving the profession altogether.

"This is why families are put in a situation that they need to start to do some of the care because nurses are having double, triple workloads," Grinspun added.

For the association, those solutions include raising bonuses, repealing wage limits, and speeding up licence processing for internationally educated nurses to relieve pressure on the health-care system.

Grinspun said bringing in retired nurses to act as mentors would also help alleviate the burden, as well bringing in more nurse practitioners to support hospital staff.

"Now is the time because, you know, a few months from now it may be too late," she said.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports