MLB's expanded playoffs: Who gets in? Will randomness prevail? And does best team win the World Series?

For just the fourth time in 54 years, Major League Baseball is making significant alterations to its playoff format. Yet in a sport that prides itself on the sanctity of 162-game regular seasons, that’s frequent enough to provoke reactions ranging from skepticism to panic.

Come October, baseball’s postseason will look nothing like it has before, a vast departure even from its last alteration in 2012. The gates will be flung open wider than any season, with three wild-card teams from each league joining the three division winners.

The wild-card games are dead, replaced after a decade-long run, by best-of-three series in which the higher seed will host all the games. And the top two division winners in each league, in a nod to regular season achievement, will receive first-round byes and await the survivor of the top two wild-card qualifiers in the Division Series.

It is all very un-baseballey as we knew it, what with seedings and byes and the fulfillment of commissioner Rob Manfred’s desire to marry a playoff format with the modern fan’s love of brackets. Manfred and the owners, in fact, aimed for 14-team fields before collective-bargaining talks with players yielded an expansion from 10 to 12 teams.

And little wonder. While the game’s unwritten rules may evolve, players may never cede their undying respect for the grind – and their worry that a too-loose playoff format may infringe upon its meaning.

“I’m always concerned it gets watered down and becomes like the other sports, where the playoffs is such a long ordeal,” says Arizona Diamondbacks closer Mark Melancon, who has reached the postseason with three franchises. “I think it’s pretty special when you really, really have to earn it. It makes that 162 really valuable.”

As baseball’s postseason grows, it’s worth pausing to ponder if baseball’s playoffs have and will continue to serve their purpose.

In short, does the best team in baseball win the World Series? Do expanded playoffs reward the greatest teams, or the hottest ones?

And after nearly three decades of the wild-card format, should we re-think the apparent legacies of franchises we’ve deemed October failures?

NEW FORMAT: MLB's playoffs are about to get bigger – but will they be better?

FOREVER A RAY: Kevin Kiermaier nears the end after outlasting bigger stars

SPORTS NEWSLETTER: Sign up now for daily updates sent to your inbox

'Holy cow, we are good'

It used to be so simple: Win the pennant, and you’re in the World Series.

Oh, there were no divisions, far fewer teams and for a long while, no West Coast travel. But the major leagues in the post-World War II era, which saw integration and expansion deepen the game’s reach, seemed ripe to reward regular season machines and budding dynasties.

For a five-season stretch from 1947-51, the team with the best regular season record also won the World Series – four championships for the Yankees and in 1948, Cleveland’s most recent title.

And from 1966-68, this era closed with the 97-win Orioles, 101-win Cardinals and 103-win Tigers backing up their regular season superiority with World Series championships.

Then, divisional play began, and the Commissioner’s Trophy became far less of a sure thing.

While no one’s clamoring for a return of two, 10-team leagues (that’d now be 15 each) and a postseason that ends sooner than a Netflix miniseries, the correlation between regular season greatness and a World Series ring has diminished.

From 1946-68, with just two teams involved, the team with the game’s best record won 12 of 23 years, or 52%, a bit better odds than a coin flip. When divisional play was introduced in 1969 and the field doubled to four teams, that number was cut by nearly half – to 28% (7 of 25).

And somewhat surprisingly, those odds remained virtually identical with the introduction of the wild card in time for the 1995 postseason, as the regular season wins king claimed the World Series in just seven of the past 27 postseasons, or 26%. That includes the last 10 seasons that featured two wild cards per league with a play-in game for nine of those years, and an expanded 16-team field during the pandemic-stricken 2020 season.

Along the way, some great teams fell short of a title.

The 1980 Yankees equaled the ’98 and ’09 Yankees with 103 wins – and won more games than their ’77, ’78, ’96 and ’99 champs – yet lost the ALCS to Kansas City. The Braves had 101-win teams tripped up by wild-card winning – and eventual champion – Marlins teams in 1997 and 2003.

The 2001 Seattle Mariners equaled a record with 116 wins – but could not put away a 95-win Yankee team in the playoffs. And the existence of the wild card permitted the 93-win Nationals into the 2019 tournament, where they vanquished the 106-win Dodgers in the NLDS and 107-win Astros in a seven-game World Series.

Best team wins? Depends on your definition.

“If you look at 2019, our Nationals team, I don’t think, was better than that 2019 Dodgers team,” says Daniel Hudson, now a Dodgers reliever who was part of a six-man Nationals pitching crew that absorbed almost all the high-leverage spots in those playoffs. “But there was something going right for us that year. All of our starting rotation was pitching well at the right time, we were hitting really well at the right time.

“If you look at win-loss record and actual roster construction, I bet you a lot of people would say that the 2019 Dodgers were better than the 2019 Nationals. They might say the 2019 Astros were better than the 2019 Nationals. I think it’s just the beauty of this game. We were playing well at the right time and ended up being the best team in baseball that year, regardless of record.”

Charlie Morton, the Braves’ 38-year-old starter, has witnessed the modern postseason through virtually every lens, beginning with three consecutive trips to the wild card game with the Pirates, winning Game 7 of the World Series with the 2017 Astros and advancing to the 2020 Series with Tampa Bay after the pandemic-shortened, expanded-playoff 2020 season.

Last year, his 88-win Braves found new life late in the season, stormed into the World Series and, almost as stunningly, won it after Morton suffered a broken foot midway through his Game 1 start.

Morton’s diversity of experience has only clouded his perception of postseason fairness.

“Does the best team win the World Series?” he asks, repeating a question posed several minutes prior. “I don’t know how to answer that question. It’s really subjective.

“By the World Series, most issues are ironed out. You’re seeing two teams going at it and it comes down to will. A lot more than it does in April. Because of what was happening within the (2021 NL East), we were able to iron out a lot of stuff. It happened organically.

“We were fortunate we were in a division where the race was really tight, we got hot and it was like, ‘Holy cow, we are as good as we think we are.’”

Atlanta’s 88 wins were the fewest by a Series champion since the 2014 Giants rode a wild card berth to a third title in five years. Yet the Braves also won the NL East for the fourth consecutive year, and the title felt more like a breakthrough than an accident.

High-achieving teams are hopeful that the more inclusive format does not permit too many lightweights to crash the gates.

Bye any means necessary

To be sure, aberrations can happen in any setup. The 2006 St. Louis Cardinals won just 83 games, claimed the NL Central title on the season’s final day and startled the Detroit Tigers to win the World Series. In 1974, the Oakland A’s won just 90 games but toppled the 102-win Dodgers in October. In 1990, perhaps their best team in franchise history won 103 games, but the 90-win Reds swept them to win it all.

And just last year, the Giants won 107 games – yet drew the 106-win Dodgers in the NLDS and lost in five heartbreaking games.

Opening up the playoffs to 12 teams is a Pandora’s box, and as recently as 2017, an 80-82 team would have made the playoffs -– always a bad look.

Yet the inaugural year of this dirty dozen shootout should unfold about as well as possible.

Though nearly 100 games remain, 2022 should bring well-deserved byes for juggernauts like the 50-18 Yankees. Meanwhile, four AL wild card hopefuls are already playing .537 ball or better, and five NL non-division leaders are at .529 or better. Parity may produce a losing playoff team some year, but not this one.

Still, concerns over inequities remain – most notably for that third division champ that doesn’t receive a bye.

“If we win 100 games in our division and the Padres win 98 games and the Giants win 95 games, and the Cardinals or Brewers run away with the Central and win 101 or 102 games, are they the better team, really, to get the bye?” wonders Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner, whose team does not have the luxury of beating up on NL Central also-rans in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Chicago.

“That’s the hardest part about it. The West is obviously the best division in the National League and it’s going to be a grind all year, probably, trying to run that down. And you look at some other divisions, it might be a little longer runway. If you’re playing against better teams all year and win your division, I feel like you should be rewarded for that, as opposed to not getting a bye.”

Come 2023, the demise of the unbalanced schedule – and the wrinkle that all teams will play everybody at least once – will allay many of those concerns. Still, teams will be vying for similar berths having played unidentical opponents, which will remain an issue in the absence of an RPI-style strength-of-schedule element.

Regardless, the playoffs will be crueler more often than they are kind – especially with more participants to wreck the best-laid plans of would-be dynasties.

Ring of fire

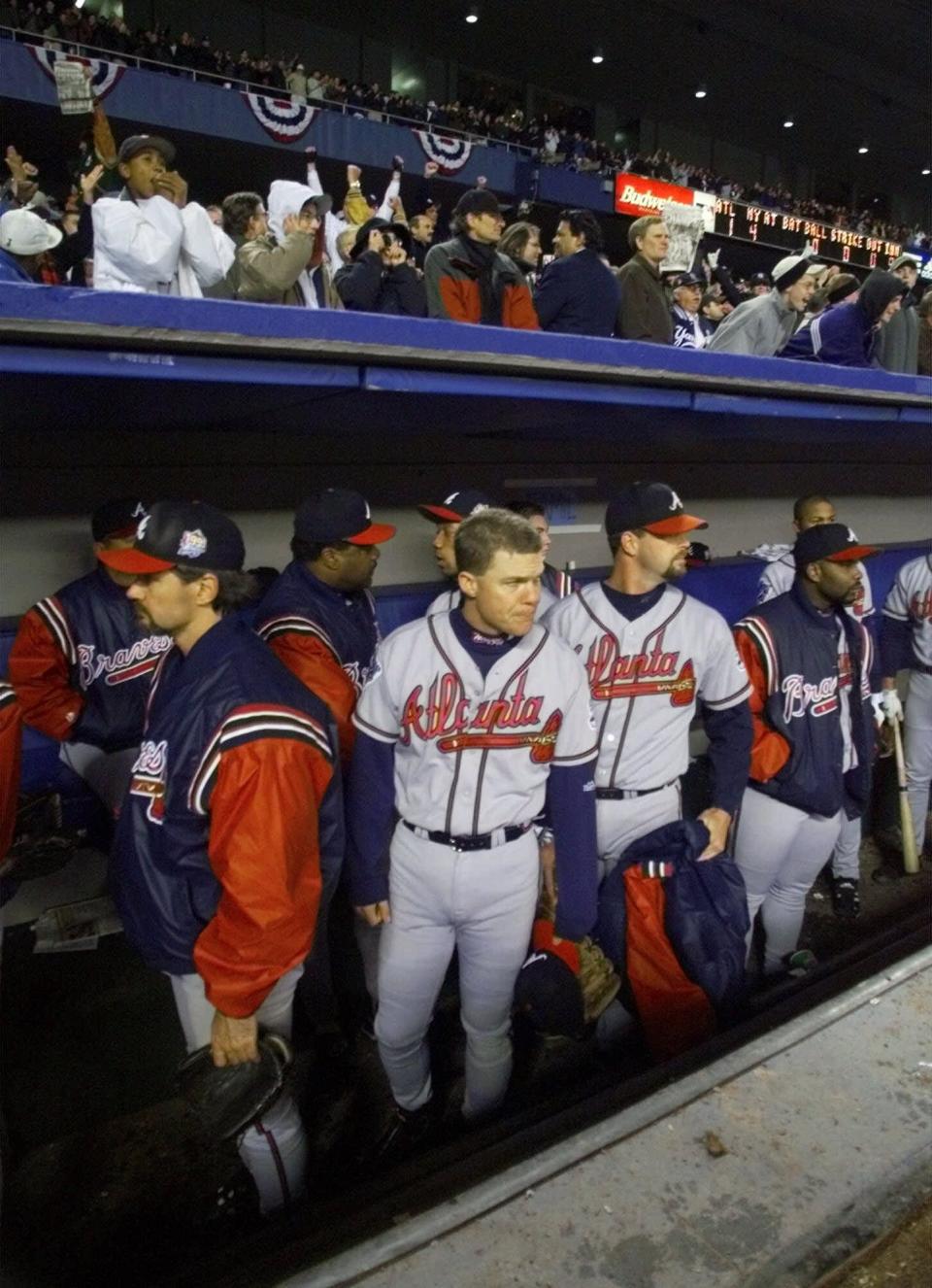

Google “Atlanta Braves and Buffalo Bills” and you’d have enough reading material for a nonstop flight to Europe.

Both teams dominated in the 1990s and became known for playoff pratfalls, but those Braves do have a championship to their name – the 1995 World Series. Nonetheless, despite winning 14 consecutive division titles, that Atlanta cohort became almost as known for playoff disappointment as regular season dominance.

In hindsight, perhaps the judgment is a little harsh.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in nearly three decades of baseball’s wild card era of playoffs, it’s that titles are elusive and October increasingly impetuous. After all, there’s now a modern team getting close to Atlanta’s division haul, with similar jewelry to show for it.

Turner’s Dodgers team won seven consecutive NL West titles and made the playoffs an eighth year as a wild card only because their 106 wins were one shy of the Giants’ 107. Their lone championship came in 2020’s shortened season, largely amid a playoff “bubble” in San Diego and suburban Dallas.

Are the Braves of Glavine-Maddux-Smoltz and the Kershaw Dodgers choking disappointments? Or does the latter’s existence – and championship frustration – justify the late October struggle of the former?

And does the “how many rings?” lens through which we now view sports ring hollower thanks to the randomness of baseball compared to, say, another odious LeBron vs. Michael debate?

“There’s a lot to be said for the Braves winning their division 14 years in a row,” says Turner, whose current Dodgers team boasts former MVPs in Clayton Kershaw, Cody Bellinger, Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman. “We did it seven years in a row and obviously won 106 games last year and didn’t win the division.

“You just can’t compare baseball to basketball. Basketball, you get these superteams, you recruit three players and those three players can dominate games. You can have three or five of the best players here, but still have to rely on the other 20 to do their part, or you’re not going to win a lot of games.”

Braves catcher Travis d’Arnaud, like many baseball fans of a certain age, grew up on the ‘90s Braves, coming home from school in suburban Los Angeles to catch Atlanta games on TBS, watching more innings of Skip Caray than he did Vin Scully since bedtime would arrive by the time the Dodgers game ended.

He’s seen both ends of playoff cruelty, his 2015 Mets stunning perhaps the best Dodgers team of this vintage in the NLDS on their way to the World Series, while splitting NL pennants with the Dodgers the past two years.

He drilled two home runs in the 2021 World Series and suddenly, finds himself with as many rings as Chipper Jones or Tom Glavine – not that he’d besmirch their accomplishments.

“To win the division that many years in a row is crazy,” says d’Arnaud. “I’ve only been a part of two in a row here and it seems like a lot already. They did 14? It blows my mind.”

“You’d think they would’ve won more,” Melancon says of those Braves and these Dodgers. “But it’s really hard to do.”

It may only get harder. More opponents, more rounds, a stunning upset – there’s simply more outcomes on the table when more games are played. That’s about all we can take from history both modern and well-worn: The bigger the dance, the greater chance that hearts will be broken.

“I think that’s what makes our sport so great,” says Hudson, “and why we love it so much. How much randomness there actually is to our sport and how beautiful that is.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: MLB's new playoff format: Does the best team win the World Series?

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports