Last of the old-school coaches: After 39 seasons, W&M’s Jimmye Laycock hangs up the whistle

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. – The College of William & Mary in Virginia measures time in centuries. The second-oldest university in the country after Harvard, it’s more than 80 years older than America itself. So in a way, it’s fitting that the longest-tenured coach in college football would set up shop here among the red brick and ivy.

You might not know the name Jimmye Laycock – heck, you might not even know where William & Mary itself is located – but you’ve seen the results of his handiwork. From a tiny stadium in southeast Virginia, he’s led and inspired Super Bowl winners and Super Bowl record-holders. He’s never won a championship himself, but those who learned from him have. And on Saturday, after 39 years in green and gold, he’ll call it a career.

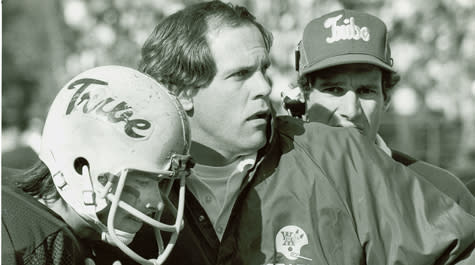

After nearly four decades on the sidelines, Laycock’s got a little less hair under the green Tribe ballcap, and a little more paunch over the khakis, but he’s still got a classic bull-necked coach’s look, his voice raw from four decades of sideline shouting. Nick Nolte would play him in the movie of his life. Going into Saturday’s finale, he’s led the Tribe in 445 games, winning 249 of those – both figures ranking Number 1 among active Division I head coaches.

Plus, he’s done it all without running afoul of the NCAA, amassing exactly zero major NCAA infractions in his tenure. Indeed, the only time William & Mary ran afoul of the NCAA under Laycock came in the mid-2000s, when the NCAA ruled that the feather – yes, the feather – in William & Mary’s logo might be offensive to Native Americans. (Known as the “Indians” when Laycock took over, William & Mary changed its mascot to the “Tribe” in the early ‘80s.)

He’s a rock in a profession built on shifting sands, the longest-tenured coach in college football. The current FBS leader, Kirk Ferentz at Iowa, came on the job 19 years after Laycock started. Back during Laycock’s first season, Nick Saban was an assistant at Ohio State. Urban Meyer and Jim Harbaugh were juniors in high school. Dabo Swinney was still in elementary school. And Lincoln Riley was three years away from being born.

He’s one of the last remaining links to the pre-corporate days of college football, and oh, does he have stories to tell.

The good old days weren’t always so good

“I didn’t expect, when I came to William & Mary, to be here for umpteen years,” Laycock told Yahoo Sports from his expansive, wide-windowed office in W&M’s Jimmye Laycock Football Center. “I’d been moved around as an assistant every two or three years. But it’s what I am, it’s what I do, it’s what I’ve been doing. I enjoy the place.”

Jimmye Laycock – his mother gave him the extra “e” on the end of his name to make him stand out – was a jock from birth, a three-sport, four-time letterman in high school who went on to play football at William & Mary in the late 1960s. Without even realizing it, he was getting a literal Hall of Fame education – he played under future Bills coach Marv Levy his first three years, and future Notre Dame legend Lou Holtz his last. (According to local legend, Holtz, who went 13-20 in three years as the coach at W&M, was asked why he didn’t win more in Williamsburg. “Because I had more Marys than Williams,” he supposedly said, a quote that surely wouldn’t travel well in 2018.)

After college, he coached and taught high school just down the road in Newport News, Virginia. But the pull of the sideline was stronger than the lure of the classroom, and he began the life of an itinerant assistant coach, stopping at Clemson, the Citadel, Memphis State (now the University of Memphis), and Clemson again. Under Charlie Pell and Danny Ford, Laycock’s offense helped Clemson win an ACC championship.

“I felt like when I got into coaching that I had a good foundation of fundamental football because of the exposure I’d gotten with Marv and Lou,” he said. “I felt like I understood football. So when I went down to Clemson as a GA (graduate assistant), I was pretty far along. I knew some stuff.”

Enough to land him the William & Mary job – a three-year deal starting in 1980 at the princely sum of $32,000 a year – but not enough to win many ballgames. The Tribe played N.C. State in Laycock’s very first game, and lost in a squeaker, 42-0. And it didn’t get much better from there.

“William & Mary was always a strong academic school, but football-wise, it was erratic,” Laycock recalled. “But a lot of people would make the excuse that, ‘well, we may have gotten beat, but our players are smarter than their players, our SATs are higher than their SATs.’ That was one of my main goals, to eliminate excuses. I wanted to establish a football program that’s comparable to the university.”

It was a hell of a hill to climb. The obstacles facing Laycock in those days were flat-out laughable. The team would practice out at open fields a couple miles from the university, on grounds adjacent to what was then known as Eastern State Mental Hospital. Patients at the hospital with permission to wander the area would walk straight across practice fields and, on occasion, stop and talk with players in the midst of practice.

If it rained, the team would practice on the parking lot of the basketball arena, with offense and defense flipping a coin to see who got to go downhill and who had to fight uphill. “We had to sweep up broken bottles. One kid got hurt running into a bike rack,” Laycock smiled. “Yeah, it was a challenge.”

And the hits kept coming. The final game of Laycock’s first season was at Richmond, on the Spiders’ artificial turf. One problem: the Tribe didn’t have turf shoes. So Laycock dispatched an equipment manager to drive down to Clemson and borrow their turf shoes for the weekend. For another road trip, the regular bus driver got stung by a bee and couldn’t drive, and the backup got into a screaming fight with his girlfriend as she dropped him off to handle the bus – which, naturally, had no air conditioning.

“There were a lot of things that made it tough,” Laycock laughed, “but even then, we weren’t making excuses.”

Laycock’s Tribe finished that first year 2-9. The next year, 5-6. The third year: 3-8. Football dominance was, to put it politely, slow to come to Williamsburg. Back then, Laycock was doing everything, right down to stuffing envelopes with tickets for players for away games. He intended to give the best tickets to the players who’d performed the best that week, but “it didn’t matter – nobody came to the games anyway.”

Recruiting from a smaller pool

Laycock was building a foundation under restrictions not generally placed on many football teams; his players had to meet the same demanding academic standards as any other students. “It’s not easy. The pool that we recruit in is much smaller than other people have,” Laycock says. “But it’s something that we accept and we understand.”

Laycock’s ethos is a simple one: bring in solid players, develop them over the course of several years, so that they’re better when they get older. “When we bring in a new coach that hasn’t been in this environment, we’ve got to educate them in regards to it,” Laycock says. “I don’t want to hear about the guys we can’t recruit because of academics. Don’t worry about the ones we can’t get, get the ones we should be getting. Get the ones that are good students that can play.”

Given the limitations of his pool, Laycock structured an offensive identity geared to his players’ strengths – fast-moving, wide-open spread offenses that moved the ball up and down the field in a hurry, years before that style took hold across the country. He turned down offers and options to leave for destinations ranging from Duke to Boston College to the San Diego Chargers, each time reasoning that he had it better in Williamsburg.

And the longer he stayed, the more success he saw. Laycock rode that wide-open offensive style to 10 postseason appearances, most notably a 2004 run that featured William & Mary facing rival JMU live and nationwide on ESPN2. For that night game, ESPN had to bring in truck-mounted lights; Zable Stadium didn’t have lights at the time.

Plus, there were the times William & Mary knocked off in-state rival Virginia, upsets huge enough that the Tribe could gloat about each one for a decade:

Those kinds of wins were few and far between, particularly for a school as small as William & Mary. The Tribe’s football program brought in revenues of $6.5 million in 2016, the most recent year in Department of Education reports; by comparison, Alabama football brought in $108 million, and Texas football, $141 million. (Worth noting: William & Mary had as many wins – five – as Texas did that year.)

So William & Mary looks for other ways to measure success. Like, for instance, the way that Tribe football has expanded with the creation of the $11 million Laycock Center in 2008, and a $28 million renovation that added luxury boxes to the brick-and-aluminum-benched Zable Stadium in 2016. Or the fact that so many of Laycock’s players have graduated and gone on to productive careers. Or, from a football perspective, the fact that three of Laycock’s proteges are head coaches in the NFL right this moment.

It’s not a bad legacy.

Successes beyond the field

This Saturday, hundreds of Laycock’s former players will gather at W&M to pay tribute to the man at halftime. Most of them never got any closer to the NFL than the TV remote on a Sunday afternoon. But their victories are on a broader level – lawyers, doctors, CEOs and politicians, all of whom spent days grinding it out under the sound of Laycock’s whistle.

Of course, there are a few notable football-related successes to come out of Williamsburg. The Pittsburgh Steelers’ Mike Tomlin, the Atlanta Falcons’ Dan Quinn, and the Buffalo Bills’ Sean McDermott all learned under Laycock, and have all reached the Super Bowl, Tomlin and Quinn doing so as head coaches.

Quinn, who led the Atlanta Falcons to the Super Bowl two years ago, began his coaching career under Laycock as a defensive coordinator in 1994. And even though he got the typical rookie hazing – in his first meeting, other coaches guided him to an empty seat that turned out to be Laycock’s – Quinn picked up lessons from Laycock even in his brief time in Williamsburg.

“You could see that personal connection that he had with individual players. It was an excellent team for me to be a part of,” Quinn told Yahoo Sports recently. “There were some NFL players there, but his ability to have these small connections with different guys [meant] a real clear vision of how teams would play.”

“I could tell when he was here that he had the ‘it factor,’” Laycock says of Quinn. “He had the wherewithal, the initiative, the decisionmaking personality. I could tell, ‘he’s going to be a good one.’”

McDermott, now in his second season with the Bills, gets similar praise: “What an overachieving player. He was a walk-on who earned a scholarship and became a starter and then a captain,” Laycock says. “An all-around good guy. I had him for a year [after he graduated] and wanted to keep him longer, but he went with Andy Reid [to the Eagles organization]. I knew if he decided to stick with coaching he’d be successful.”

Quinn’s one-year tenure at William & Mary in 1994 overlapped with both the freshman year of McDermott and the senior year of another guy who’d go on to have a bit of success in the NFL, a wide receiver by the name of Mike Tomlin. Under Laycock, Tomlin – the future coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers – set school records by averaging 20.2 yards per reception his senior year and totaling 20 touchdowns over his career. But it’s Laycock’s coaching style that’s stuck with Tomlin, literally right up to the present.

“That guy’s been on his job 39 years,” Tomlin said just after Laycock announced his retirement. “What better mentor to be able to call and share some experiences and gain some perspective?”

“Tomlin made the best catch I’ve ever seen, one time against UMass,” Laycock recalls. “When he won the Super Bowl, I called him up and said, ‘That (Santonio Holmes) catch that won it was almost as good as yours.’ He said, ‘Yeah, coach, but the stage was a little bit bigger.’”

Tomlin noted that the phone call he got from Laycock about retirement summed up their entire relationship. “We didn’t spend a lot of time talking about his retirement,” Tomlin said. “He acknowledged it, and then we quickly talked about how to meet the challenges that await this year. That’s him. He taught me that … He’s a singularly focused, professional guy. You felt it when you played for him. You always felt supremely prepared, because he exuded confidence that was steeped in preparation.”

Time to close the book

Time rolls on, even for icons. Laycock gave up playcalling duties in 2013, the first of his many unravelings from the program. On the field, William & Mary has suffered through a few rugged seasons, posting losing records the last two years and, at best, a .500 mark in 2018. At the administrative level, the College has both a new president and a new athletic director. The time’s right for wholesale change.

The student body’s changing, too. Granted, William & Mary is a school that – let’s be honest here – gets a lot more fired up for, say, the arrival of Chick-Fil-A on campus than a football game. But even so, football is losing its preeminent status among students.

“Football is much more for the alumni at this point,” says Brendan Doyle, who covers football for The Flat Hat, the College’s student newspaper. “Everyone recognizes and appreciates what [Laycock] meant to the school and the program. But students now are much more interested in basketball than football.”

At 70, Laycock owns a nationally prestigious resume – but he also still has his health, and he has goals, the kind of goals he could never set while he was coaching. “I want to go to the beach in August,” he said at his retirement announcement before the season started. “I want to tailgate in September, and I want to play golf in October. I’m a man of simple means, I really am.”

____

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Contact him at jay.busbee@yahoo.com or find him on Twitter or on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Tampa in model’s crosshairs after husband’s MLB snub

• Ex-Cowboys star comes out as gay decades after retiring

• Steelers’ cruel goodbye to Bell is revealing

• Mexico shamed, fans angered by NFL debacle

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports