Inside the greatest ad EVER: Nikes brilliant 1998 Brazil airport commercial – by those who made it

Twenty years ago, on a Wednesday night in north London, a young film editor went to the pub to watch football. Unlike his fellow drinkers, England’s World Cup warm-up in Switzerland was not foremost in his mind.

“At half-time, the commercial came on and everything went a bit quiet,” says Russell Icke. “That was quite unusual. And then when it finished, three or four people near the screen started clapping. It was the highlight of my career at that point and is still one of my highlights today.”

The applause was for Airport 98, the game-changing Nike spot which deposited a handful of irrepressible Brazilians in the sterile environment of a terminal, roped in a Hollywood director who Ronaldo says “told us to do karate moves, Matrix moves”, added a decades-old samba classic and created 90 seconds of magic which resonates to this day.

Says Pierre-Laurent Baudey of Nike, “I think it's iconic even now because it was the first occasion of a brand making such a splash around a soccer tournament. Now it’s expected and anticipated that Nike will come out with an epic. Back then, we were taking football into a new space.”

Now global director for consumer strategies at the sportswear giant, Baudey was the company’s advertising director for football in 1997. Back then, he was piecing together a sponsorship deal with the then-world champions which would pay the hitherto cash-strapped Brazilian FA some £250 million over the cycle of three World Cup finals.

“We were starting in football,” he says now. “We wanted to be the No.1 sports brand and to do it we had to be the No.1 football brand, because we knew it would be hard to do it without football. Signing the Brazil team was the beginning of our journey.”

Making boring brilliant

With Nike theoretically shut out of France '98 by dint of Adidas’s official sponsorship, the upstarts green-lit a campaign of ambush marketing reckoned to have cost around £24 million. That would pay for the impressive Nike Park fan zone at La Defense; the ads running down the sides of Paris skyscrapers and apartment blocks; the travelling roadshow which took a team of Nigerian U18s to some of the country’s remotest outposts to play local sides on a synthetic pitch which rolled out of their coach. At the centrepiece, though, had to be a commercial which made the world sit up and notice.

To that task, Nike entrusted the creative agency of Wieden+Kennedy, with whom they had been working since 1978.

Says Baudey: “We went around the world, talking to kids. The feeling was that the game was getting a bit boring. The 1990 World Cup final was boring - I can’t remember a more boring final. The ‘92 Euros which Denmark won had a low goal average. Brazil had won in ‘94 but only on penalties, and Euro '96, though I know it meant more in England, was not a great tournament.

“The feeling was, ‘Is this really it? Is this what football is about?’ At the same time we noted the rise of the small-sided game and the way it was felt to be more spontaneous and creative and soulful. That was our starting point – that the game needs to be played with creativity and spontaneity. Attacking football. It begins there. And who epitomises it? Brazil. Then you unleash the creatives with that brief.

“W+K came back with some options, storyboards. They briefed a number of teams - Amsterdam, Portland, Tokyo. I remember seeing work come back from every office. The one we saw which looked really cool was from John Boiler and Glen Cole in Amsterdam. I’m sure I’ve seen more impressive storyboards before but this had the potential to deliver in ways we didn’t expect. It was set somewhere footballers spend a lot of time, just waiting for planes.”

Speaking on the shoot in 1998, Boiler - still working on Nike campaigns with Cole as co-founders of the U.S. agency 72andSunny - explained: “The whole premise of the spot was what happens when you get a bunch of these football stars who are really like kids... trapped in the most boring place in the world - an airport.”

The original storyboards that he and Cole had worked up called for each player to perform his signature tricks in remote parts of the airport while waiting for their flight to France. So far, so promising – but Nike’s next move would deliver a jolt of kinetic energy.

Woo and the crew

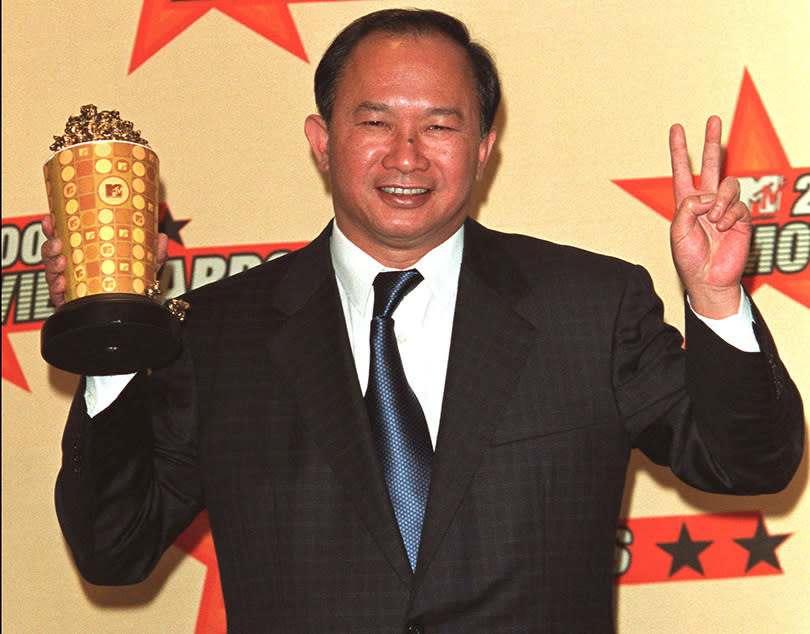

Born in Guangzhou in 1946, John Woo’s stock among the creative community had rarely been higher. Arriving in Hollywood in 1993 after his pulsating Hong Kong-set action thrillers A Better Tomorrow, The Killer and Hard Boiled won the patronage of Quentin Tarantino - who with characteristic understatement, compared Woo to Michelangelo - he had followed a couple of mid-budget misfires with 1997’s stylish blockbuster Face/Off.

Cole and Boiler loved his ‘bullet ballet’ style (“when John films, it’s like a dance; nothing is ever photographed in a mundane fashion," raved Cole), and noted that both The Killer and Face/Off featured key scenes shot in airports.

Despite never having filmed a commercial before, Woo signed up and quickly added his own stamp. The director wanted, he later explained, “to produce a musical commercial that showed the beauty and energy of the players and the product.” To do that, he added in the concept of players navigating a series of obstacles which Boiler said allowed them to “look spontaneous and natural by letting them just play soccer. It was a brilliant way to handle the problem."

But as teams assembled - Woo, Boiler, Cole, producer Charles Wolford, director of photography John Tattersall and cameraman Nicola Pecorini leading the creative side; Ronaldo, Romario, Roberto Carlos, Denilson, Juninho and Leonardo among the on-screen talent - many more problems lay ahead.

Filming was pencilled in to begin at a private VIP departure lounge at Galeao International over Christmas 1997. “We had to work around Christmas and the New Year,” explains Baudey, “because apart from Romario, who was back at Flamengo, the players were scattered around Europe - Milan, Madrid, Seville.”

With part of the schedule only being confirmed three days ahead of filming, Woo’s agency A Band Apart pulled strings and stretched budgets to grab last-minute plane seats for the principals and freight flights for tonnes of equipment – both tough asks during the holiday period.

Yet getting everything and everyone to Brazil in one piece proved to be only the beginning of the challenges. “I can’t tell you how chaotic it was shooting during the holiday in an airport where nobody wanted us,” Tattersall said in 1998. “If you need something in Brazil it’s three days away, or that office is closed for the month.”

Though they came prepared for heat and humidity, the crew were also taken aback by the ferocity of the weather in a shoot which called for some outdoor shots. Says Baudey: “It got upwards of 45 Celsius. Just imagine being on that tarmac! Juninho was getting ready to do his scene underneath the met and the cameras were melting.”

Indeed, they were so hit that crew members couldn't remove the film magazines in fear of damaging the stock. Meanwhile, local airline Varig, whose maintenance hangers were being used for certain shots, fretted that the combination of the outside temperature and the film-makers’ lights would melt their planes’ windows.

No one felt better either when more extreme weather was forecast. Says Wolford: “The most taxing moment was the impending thunderstorm that was approaching the airport, in 120 degrees Fahrenheit on the tarmac, and we had one opportunity to shoot the 747 scene. That was the most tense moment of the production.”

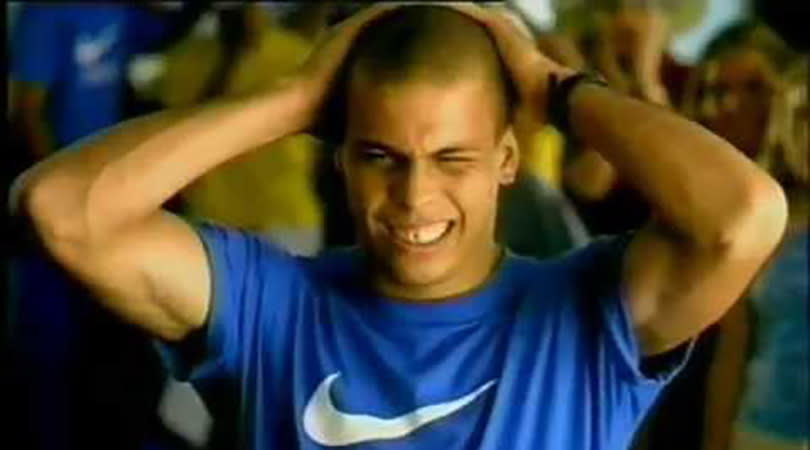

Into this overheated atmosphere came the players. “It was a very easy-going team; the younger learned from the elders, and the elders got energy from the younger,” remembers Ronaldo. “Neither I nor anyone in the team had done any acting. But we just gave it our all. We all feared not doing well, but I guess it worked for all of us because there were no lines to say. It was all about running and looking interested.”

But at Christmas in Brazil, there is only so much running and looking interested that one can do. “It was like working with multiple rock stars all at once,” says Wolford. “What we forgot was how much Brazilians like to party over Christmas and New Year,” adds Baudey. “It was hard to gather them in one place. Some people wanted to be on the beach, and I remember once Romario bringing Ronaldo back from the beach, where they’d been at a tournament. It felt like he was bringing his little brother to the shoot.”

Things might have been more taxing for both camps had it not been for the presence of Woo, whose Face/Off was already a favourite of Ronaldo’s. “It was fun,” says O Fenômeno. “It was like being in an action movie. John Woo gave us crazy ideas.”

First among those was to be spontaneous. “There was a lot of improv,” says Ronaldo. “Denilson’s moves, my hitting the metal bar, it was all improvised.” Adds Baudey: “A lot of the choreography was inspired by the way the players were reacting to the shoot. It was fitting that it happened that way. They'd been thrown in the middle of this after only being with Nike for a few months. But they were having fun, you could tell. John brought a fresh perspective. It was contagious. We had a lot of fun on that set.”

Woo’s craft was appreciated too. Despite having already worked with Michael Gondry on the award-winning Levi’s ad Drugstore, Icke was in awe of the master from Hong Kong. “I felt under enormous pressure but he was a lovely person who looked after this young lad, fresh off the block,” he says. “John shoots action in a different way to everyone else. Most directors like a wide shot with a close-up of the same thing. So you get one shot from two different perspectives.

“What John does, the brilliance of him, is that he will use three or four different cameras on a single shot. So you have three or four different shots. You get this amazing coverage and then that’s what the editor begins with. You have all the shots and you have to find the film from there, but it makes it easy. I should mention that he’s also a culinary genius. Every meal we had on that project was an amazing experience.”

For Baudey, that included “John and I having dinner one night when he kept talking about bringing so many people from so many different backgrounds together and having them playing like kids.” The combination of art, sport and food created an on-set vibe so positive, says Icke, that “I remember Ronaldo sitting around one day saying ‘we’re going to win five World Cups’.”

One-take Rom

Despite all the obstacles, filming in Rio produced several golden moments. “Romario is an incredible character,” says Baudey. “He had a ton of charisma. His scene was one the art director was worried about, so when we asked him to kick it through the x-ray machine, all of us were watching and he did it first time. We had to say, ‘Hey, one more time’ because it was so incredible. One of the other most difficult scenes was Denilson dashing through on the moving walkway. When he did that, all of us felt, ‘We got it, we got it.’ We were in the zone.”

Production progressed to Milan’s then-unopened Malpensa airport at the end of January, where Inter’s star man was contracted for one more day’s work which contained his signature scene. Says Baudey: “Ronaldo was very young, not even 22 then. He was still very quiet and extremely composed. And he delivered. At Malpensa we shot the final scene, of him hitting the post. We actually said to him, ‘do you think you can hit the post from there?’ He did it first time, then he did it again. He just kept on hitting that post and we kept filming until he missed it.”

One more shot remained and it was filmed in Barcelona airport shortly afterwards. The filmmakers originally planned for a reaction shot from Diego Maradona, but quickly understood that would not be possible because of the rivalry between a Brazil and Argentina. “So we reached out to Eric Cantona and his cameo was written on the set,” says Baudey. The Frenchman was a huge Woo admirer and was not disappointed by his brief encounter with the director. Three years later he would name his choice to succeed Sir Alex Ferguson at Manchester United as simply “John Woo”.

Final editing was done between Toronto and London, where Woo introduced a surprise guest. “Malcolm McLaren (former Sex Pistols manager, then attempting a Hollywood career) was there with us,” says Icke. “He was attempting to persuade John to direct some project or other. John was signing promotional footballs and one of my strangest and most prized possessions now is a football signed by Ronaldo, Leonardo, John Woo and Malcolm McLaren.”

Baudey had left the shoot feeling positive. Soon he would be euphoric. “It's always hard to know without having a total view, but every shot we had in the bag we knew had something special,” he says. “Then we saw the first trailer and we were still super-excited.”

Bit of a Blur

The jigsaw Icke was assembling was still missing its final piece, however. “Music is always a nightmare,” he says. “The very first music I edited to was a version of All Of Me, the 1930s song, but sung in Spanish. That looked great on the film but it felt too slow.” Says Baudey: “We tried a lot of different tracks. At one point we had Song 2 by Blur. Everybody loved it.”

Apart, that is, from Icke. “I thought it would have thrown the edit into chaos,” he says. “It would have turned the commercial into a montage, the kind of thing you can see anywhere.”

Adds Baudey: “Someone, and I can’t remember who, said, ‘How about something a little more soulful, less modern? At the 11th hour the agency came back with this 32-year-old piece of music.” It was Mas Que Nada, originally recorded by one Brazilian music legend Jorge Ben but heard here on the version recorded by another, Sergio Mendes, on his platinum-selling album Brasil 66. A lesson in effortless cool, its title translates roughly as 'Yeah, right'.

For the film-makers, it was just right. Says Icke: “I think we listened to something like 200 tracks and we went past that early in, but came back to it. It's so beautiful and it turns the commercial into something completely different for me.” Agrees Baudey: “It was a big decision but a masterstroke. I’m so glad we landed where we landed.”

With its soundtrack in place, together with a title which nodded at the almost-forgotten 1970s disaster movies trilogy which inspired Airplane, Airport 98 prepared for take-off on March 25, during the final round of in-season pre-tournament friendlies. Ad slots were booked around the world barring Argentina, in recognition that Nike would be wasting their money in the home of Brazil’s deadliest rivals.

The reception was pretty much as experienced by Russell Icke in his north London pub, where in the supporting feature, England and Switzerland drew 1-1. The Independent reported that, “for armchair viewers, the evening did yield some moments of spectacular action. Regrettably for Glenn Hoddle, they came during the commercial breaks. And the setting was not a football field but an airport.”

Though Brazil would return from their real trip to France empty-handed, Nike’s fictional version won plenty of silverware, including Mobius, Clio and British Design awards. Nike were further vindicated when post-World Cup research indicated that the commercial and a wider campaign of activity reportedly costing £20 million had persuaded 32 per cent of viewers that Nike were official sponsors of the tournament. Real sponsors Adidas were named as an official FIFA partner by only 35 per cent.

“It did change the world a little bit,” says Icke. “It was the beginning of an era in advertising and it is still referenced and influential.”

Adds Wolford: “I remember the shoes cleared the shelves and Mas Que Nada turned into a worldwide hit with numerous versions being created. I heard it over and over no matter where I went. I could be biased, but I still think it’s one of the best soccer commercials ever done. It had an energy and joy that came across, despite the complication of how we had to create it.”

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports