The House of Commons just had one of its slowest years in a century, thanks to the pandemic

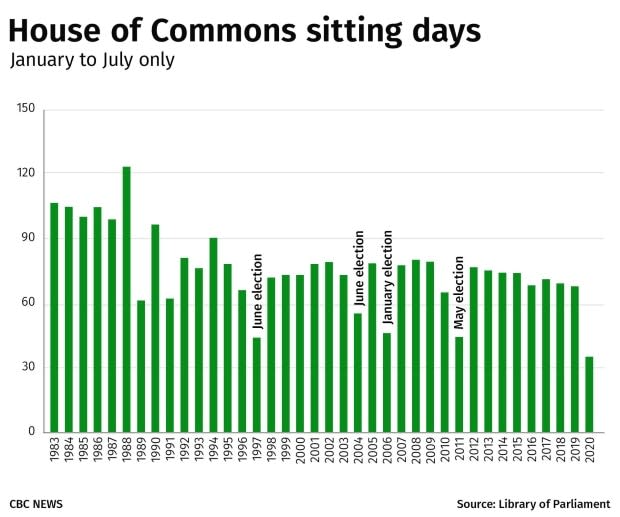

Thanks to the pandemic, the House of Commons came close this year to setting an all-time record for the lowest number of sitting days ever — a number lower than any recorded since the waning days of the Second World War.

And the Commons has never experienced a lower number of sitting days outside of an election year than it has so far in 2020 — just another example of the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 emergency.

Concerns over the spread of the virus prompted the House of Commons to adjourn in mid-March. It has returned only sporadically since then.

Since the beginning of this year, the House has booked only 33 sitting days, with two more scheduled in July. With the exception of 1945, when the House sat for only 20 days between January and July, that is the fewest number of sitting days ever.

Had the outbreak struck earlier, 2020 might even have broken that 75-year-old record. This year, the House sat for 24 days before the pandemic-induced adjournment on Mar. 13.

The frequency of sittings in the House during the crisis has been a point of contention between the parties. One compromise created a special committee in which all MPs could participate — remotely or in person — to discuss the government's pandemic response. This committee has met on 21 days when the House did not have official sittings.

These committee meetings are not the same as normal sittings of the House — bills and motions, for example, cannot be introduced or voted upon. But even counting these extraordinary sessions of a special committee, Parliament Hill has not been so quiet outside of an election year in nearly a century.

A world war and a June election

Let's put that in perspective: the only other time the House of Commons has held so few normal sittings was during the Second World War.

At the beginning of 1945, the war was coming to a victorious end but it was not clear how much longer it would last. After a bruising debate over conscription, Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King extended the House's Christmas recess straight through to the end of January.

John Bracken, leader of the opposition Progressive Conservatives, took the opportunity to travel to Europe, visiting soldiers and hospitals to get his own sense of Canada's needs on the battlefield.

On this continent, political attention was focused on an important byelection called to get the minister of national defence, General Andrew McNaughton, a seat in the House (he ultimately failed to win). Prorogued immediately after a single-day sitting on Jan. 31, the House didn't meet again until the middle of March.

It then sat for 20 days over the subsequent month before King announced an election would be held in June. He flew off to San Francisco, where he stayed for more than three weeks for the founding meeting of the United Nations. He returned in May to start campaigning and, after winning re-election, did not recall the House again until September.

The House is sitting less and less

Until there is a vaccine for COVID-19, the House of Commons might continue to meet less often than in the past. But its operations were already on a downward trend.

In the 19th century, the House generally met only in the spring; sittings rarely stretched very far into the summer and were held even more rarely in the fall or winter. These sittings also were relatively short, with the House meeting an average of 54 days between January and July in the 1870s and 68 days in the 1880s.

The House met more often as time went on, averaging between 80 and 97 days over the first seven months of the year between the 1900s and 1940s. The decades after the war were the busiest for the House, with an average of 103 sitting days per year between January and July from 1946 to 1989.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, however, the House has met less often. The House sat for an average of just 74 days between January and July in the 1990s, dropping to 72 days in the 2000s and 69 days in the 2010s — the lowest attendance rate since the days of John A. Macdonald.

The role and importance of Parliament has been debated over the last few months — and the pandemic could change how the House functions. In the future, just as more Canadians work from home permanently, MPs also might be given the option to attend and vote remotely.

But there's been little serious outcry from the public over how often the House has met lately. The Liberals are still buoyant in the polls. In the midst of a global pandemic, Parliament does not appear to rank very highly as a priority.

Whether the House will start meeting again more frequently, or continue its decades-long decline, might depend on how Canadians feel when the pandemic is over.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports