Here's how Downtown Julie Brown changed the Super Bowl

Twenty-five years ago a job offer came in for Downtown Julie Brown, the British-born actress and model who had become famous in America for sporting small skirts and big personality each afternoon on the dance show "Club MTV."

The syndicated television program "Inside Edition" wanted her to cover the Super Bowl between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Giants. Only the show didn't want her to report on it like the sports pages at the time, but to essentially do the opposite. The focus would be fun and flirtatious, centering on parties and personalities, basically everything going on in Tampa that week except football.

Today, as the game has exploded into a week of pop culture with a football game in the middle, such coverage is commonplace. In 1991, it was unheard of – the Super Bowl, especially the media coverage of it, was the domain of crusty sportswriters and blazer-clad sports broadcasters.

"At the time nobody was doing the good-time pieces," Brown told Yahoo Sports this past week. "It was all stats. I was like, 'We know all that. We know they are really good.'

"I was trying to do the fun side of the Super Bowl, 'What kind clothes do you like to wear? What song do you listen to on your Walkman?' because it was a Walkman back then. 'What tricks do you play on the other guy?'

"I freaked out," Brown said of the offer. "I was like, 'Hell yeah, let's do it.' Then I was thinking, 'This going to be tough.' I had some dabbling with sports reporters. I knew it was going to be a big thing [having me there], especially a girl wearing couture clothes.

"Then I decided, 'Let's just do it and go for the challenge.'"

On Monday the NFL will, for the first time, broadcast Super Bowl Media Day live in prime time. At Super Bowl III some reporters wandered over to a hotel pool and asked Joe Namath a few questions from a deck chair. Now for Super Bowl 50 it's at night, from a hockey arena in San Jose, Calif., where fans can pay 30 bucks to watch it in person.

It's going to be such a wondrous zoo that it's not even called Media Day anymore. The NFL rebranded it: "Super Bowl Opening Night fueled by Gatorade." In other words, it realized there's a buck to be made here.

It should've given a nod to Downtown Julie Brown, who so changed the way the "game" was covered that the question is no longer why such an otherwise mundane affair should be considered a prime-time program, but why it took so long to move it there?

"Media Day" was a logistical creation as the Super Bowl grew in popularity. Once reporters covering the run-up to the game could easily interact with players and coaches in a hotel ballroom – or by Namath's pool. Eventually it grew until there were so many people that it was moved to the floor of the stadium to give everyone space. It was held early on Tuesday mornings, an hour or so for each team.

What was big in scale, thousands of reporters mingling with players, coaches and team executives, was still small in focus. It was mostly about football, not all that different than an average NFL week.

Then suddenly it wasn't.

"Here was Downtown Julie Brown from MTV, a girl, and I was not wearing those golf pants and printed shirts walking onto the field," Brown said. "The sportswriters were like, 'What the heck?'"

Brown, who now hosts both daily and weekend shows on Sirius/XM's "90's on 9," was and remains a big fan of both the NFL and NBA. She was dressed conservatively, at least for her, but still to be noticed, like the veteran of the New York nightclub scene she was.

Her initial worry was that she would struggle to get her questions asked, that the players, crowded by swarms of print reporters, would be hard to reach. She said through her work at MTV she knew a few of the players, most notably Buffalo running back Thurman Thomas, but this looked intimidating.

It turns out, go figure, that most 20-something men were far more interested in speaking to Downtown Julie Brown than, say, the middle-aged columnist from the Akron Beacon-Journal. When she walked up to a group, everything often stopped and the player would note, "Hey, it's Downtown Julie Brown."

She became the one signing autographs and a player's cast and shaking hands. Players began asking her questions. Buffalo's Dwight Drane put his hands around her waist and lifted her in the air and discussed how little she weighed. (Two years later, Dallas Cowboys coach Jimmy Johnson was asked if he had any specific rules for his players: "Yeah, don't kiss Julie Brown.")

Brown played along with the entire thing, even jumping in on other answers in her unique way. When Buffalo's Kent Hull told a story of a time a fan asked him for his pants, she coyly interrupted: "Kent, can I have your pants?"

Later Thurman Thomas was discussing a basic inquiry about the oddsmakers expecting the Bills to win.

"I don't know why we are the favorites," Thomas said.

"Maybe it's those dimples," Brown offered.

"Oh you like my dimples?" he said with a laugh.

____________________

Brown was correct about the reaction. There was plenty of complaining by traditional media and even some columns written about her presence. This was a culture change. Brown didn't care.

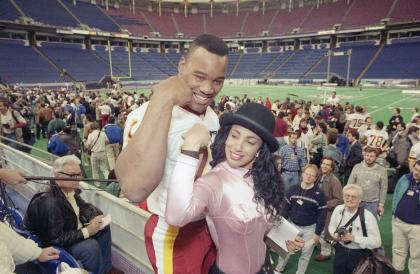

"They hammered me, 'You shouldn't have been there,'" Brown said. "There were a couple in particular that laid into me. I was kind of hurt by it but then I opened up the newspaper and there was a picture of a sea of players and sea of sportswriters and then there was me on the shoulder of one of the players."

That picture, she says, hangs in the home she shares with her husband and children.

More important, Brown was correct about something else: there was an audience for that "fun" side of things. Sure, she admits, some of it was ridiculous, but this was a football game, not a nuclear negotiation.

That year was a transitional era for the event: one foot in the wholesome, simple past, one foot in the high-entertainment future. Disney produced the halftime act with 3,500 schoolchildren singing, "It's a Small World." With the country on the verge of war in the Persian Gulf, that was overshadowed by a stirring rendition of the national anthem by Whitney Houston that propelled her to even greater stardom. Marketing around the game was about to take off.

The NFL quickly understood it was a positive if Downtown Julie Brown could get word of the Super Bowl to an audience that wasn't sports obsessed. If it tuned in to see Thurman Thomas' dimples, which your general sportswriter was not going to focus on, so what? People still tuned in. In 1990, total audience for the Super Bowl was 73.8 million. Last year's game reached 114.4 million.

Media Day went from there. Nickelodeon, with a reporter dressed as a superhero, was a regular and allowed players to speak directly to kids. All the "Entertainment Tonight" type programs and late-night talk shows arrived. MTV set up shop.

Brown covered a few more Super Bowls and even got a gig with ESPN to do softer features on players and their families for weekly pregame broadcasts.

Over the next quarter century it somehow became a contest to be more outrageous. Reporters showed up with puppets to ask gag questions. They brought musical instruments, talked in clichéd accents or asked players to sing. One of the more famous interactions came in 2008 when Ines Gomez Mont, a reporter for TV Azteca out of Mexico, donned a wedding dress and asked both Tom Brady and Eli Manning to marry her. They both politely declined.

It's been a boon to some. Over the past two Media Days, the Seattle Seahawks' Marshawn Lynch delivered the same line to all questions – "I'm just 'bout that action, Boss" and "I'm here so I won't get fined" respectively. He turned the latter into a Skittles commercial, brilliantly building his brand in an unorthodox process.

For others though, it's a challenge. There are endless, rapid-fire questions that often come out of left field and are designed for a specific reaction or require non-comedic players to play along with a comedy segment. New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick, known for his curmudgeonly news conferences, has been a prime target to get tripped up (he's managed fine). St. Louis Rams quarterback Kurt Warner, who proudly expressed his faith in Christianity, was once asked if he believed in voodoo.

At times, it's been disastrous. Before Super Bowl 47, comedian/actor Artie Lange interviewed San Francisco's Chris Culliver, using his typically light-hearted style ("Ray Lewis says God doesn't make any mistakes," Lange said, "looking at me do you believe that is true?"). It was funny. Then Lange asked if there were any gay players on the 49ers.

"Can't be with that sweet stuff," Culliver said before elaborating further.

It became a huge controversy in the run-up to the game, with Culliver and the team eventually apologizing.

____________________

The NFL isn't turning back though, if anything it is pushing forward. By moving Media Days the last three years to hockey/basketball arenas, the scene is even more crowded, a good visual but hardly something that invites decorum.

Traditional media hardly complain anymore since that ship has sailed. Besides, the NFL provides access to players and coaches all week so one sideshow night isn't that big of a deal. Sometimes, such as with Lange, who at the time hosted a sports radio show, it can create news that wouldn't otherwise have come out. If anything, Media Day isn't about generating coverage anymore but a standalone event that itself is covered.

Putting it live in prime time will likely only increase the stakes. For that, Brown is satisfied that she made an impact on the culture of the biggest sports and entertainment event in the country. She plans on tuning in Monday night. She even thinks she helped women in more regular sports broadcasting roles, by pushing the envelope so far out there the ones who came in after her in more moderate ways were welcome.

"I think I opened a lot of doors," Brown said. "Now I see a lot of women on the field. I have full respect for women reporters, I love seeing a woman down on the field. I think I set a good footprint."

Wubba, wubba, wubba.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports