The Privilege of Play: From microaggressions to acts of overt racism, why swimming isn't inviting to minority groups

“The Privilege of Play” is a Yahoo Sports series examining the barriers minority groups face in reaching elite levels of competition in swimming, racecar driving, soccer and hockey.

----

Maritza Correia McClendon wasn’t sure she heard it right. She contemplated hitting rewind and listening one more time just to make sure.

She was at her cousin’s house in Atlanta, 12 years removed from a historic Olympic moment of her own, when Simone Manuel emerged from the pool at the Olympic Aquatics Center in Rio De Janeiro and said Maritza’s name. Manuel had just become the first African American woman to win an individual gold medal in swimming, turning in an unforgettable performance in the 100-meter freestyle. But instead of focusing on herself, she used the moment to acknowledge others.

“I mean, this medal is not just for me,” Manuel said in a tearful post-race interview in 2016. “It’s for a whole bunch of people that came before me and have been an inspiration to me. Maritza, Cullen [Jones], and it’s for all the people after me.”

Four years later, the gesture still means a great deal to McClendon, who in 2004 became the first Black woman to qualify for the U.S. Olympic swim team.

“Beyond the tears, my jaw dropped when she said my name,” McClendon said. “Hearing her giving credit to those who came before, it’s amazing. I had chills, excitement and that proud feeling. We’re in this together now. It’s not just her carrying the torch; we’re all working on it together.”

With her golden breakthrough in Rio, Manuel joined an elite group of top Black athletes in swimming in the U.S., one that includes Olympic medalists Anthony Ervin, Lia Neal, Jones and McClendon. It’s a small circle, but one athletes, coaches and advocates are intent to expand. Theirs is a collective effort to bring more children of color into the water and improve inclusivity in a sport still considered predominantly white.

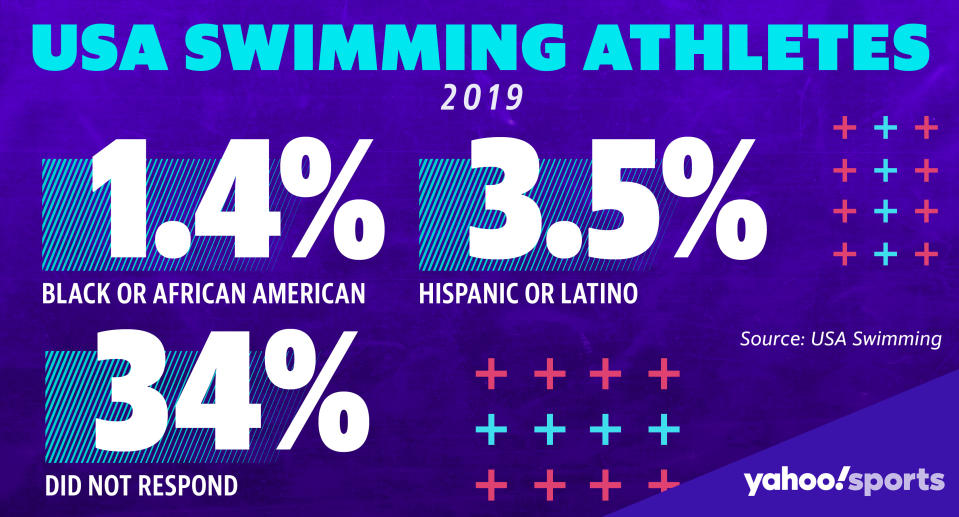

USA Swimming’s 2019 report on demographics laid bare the participation gulfs that exist. Of its 327,337 year-round athletes, only 1.4 percent (4,841) identified as Black or African-American, while 3.5 percent (11,597) identified as Hispanic or Latino. Thirty-four percent did not respond to the ethnicity question.

“Swimming,” McClendon said, “isn’t as inviting to the African American community as it should be. That is something we’re working on. … We’re seeing Simone and Lia, but who are the others? Who’s coming through at nationals? I see the change, but there are still so few of us at the national level. Change is still gaining traction.”

Disparities in swimming ability

The first step is getting children into the pool — not for visions of Olympic hardware, but for safety itself.

A 2017 survey by the University of Memphis and the USA Swimming Foundation found that 64 percent of Black children and 45 percent of Hispanic/Latino children have little or no swimming ability, compared to 40 percent of white children. If a parent doesn’t know how to swim, a child has only a 13 percent chance of learning, research shows. The negative relationship with the water can create a generational gap with potentially deadly consequences. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black children ages 5-19 are 5.5 times more likely to drown in a swimming pool than white children.

“All of us have stories of knowing someone who’s drowned in our community,” said Miriam Lynch, executive director at Diversity in Aquatics, an organization geared toward increasing water safety awareness and drowning prevention in historically underrepresented communities. “So there’s a fear. If you stay away from it, you’ll be safe. That’s the notion.”

That fear is an undeniable factor in a longstanding, complicated problem. Lynch, whose mother lost her eldest brother to drowning, points to three others: Funding, pool access and the way water is perceived as a result of centuries of repression. Indeed, it’s impossible to consider the disparities that exist today without taking history into account.

Racism at the pool

Historian Dr. Jeff Wiltse, author of “Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America,” argues “past discrimination in provision of and access to pools and lessons is the primary cause of contemporary swimming and drowning disparities.” He points to two specific periods in the 20th century to explain why.

In the 1920s and 1930s, swimming surged in popularity as thousands of large public pools sprung up in cities across the United States. A veritable “pool-building spree,” Wiltse said — but one only white Americans could enjoy. The social norms that, in some cities, kept men and women relegated to separate pools began to change, instead giving way to racist fears. As a result, the vast majority of these massive pools, complete with grassy lawns, sun decks and artificial beaches, were off limits to Blacks.

“Most whites objected to Black men having the opportunity to interact with white women at such intimate public spaces,” Wiltse wrote in “The Black-White Swimming Disparity in America: A Deadly Legacy of Swimming Pool Discrimination.”

Racial discrimination became normalized across the country, with cities in the south using Jim Crow laws to keep Black swimmers out. Those who dared enter pools in the north were sometimes turned away by force. Such was the case in August of 1931 when the city of Pittsburgh opened a new pool in Highland Park.

On the second day of the facility’s opening, approximately 50 Black men joined nearly 8,000 revelers at the pool. An article from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, which ran Aug. 6, 1931, under the headline “Police Unable to Prevent Highland Pool Race Clashes,” described what happened next. Each Black swimmer was “immediately surrounded by whites and slugged or held beneath the water until he gave up his attempts to swim and left the pool.”

The gradual desegregation of pools after World War II set off a series of events, leading whites to abandon municipal pools for private club pools or residential ones in the suburbs. When they left, the tax dollars went with them. Attendance at city pools plummeted and many fell into disrepair and closed.

In the suburbs, however, swimming again surged in popularity. Nearly 23,000 private swim clubs popped up by 1962, giving middle- and upper-class white Americans easy and abundant access to the water. These pools, Wiltse noted, represented the “seedbeds for the explosion of swimming as a participatory sport.” But again, Black Americans were almost entirely excluded.

“Swimming became an integral part of white America’s recreational culture,” Wiltse said. “Parents take their kids to these pools, and a generation of white Americans learns to swim. By contrast, there is no similar, self-perpetuated swimming culture developed in Black American communities.”

Civil rights movement takes the leap

Public pools were often regarded as a battleground of civil rights. On June 18, 1964, 17-year-old Mimi Jones joined six other activists and leaped into a whites-only pool as part of a swim-in at the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida. With cameras rolling, motel manager James Brock emerged with a jug of muriatic acid and began pouring it into the pool. Martin Luther King, Jr. reportedly witnessed the scene unfold from across the street.

The events of that day helped spur President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and a photo of Jones reacting in horror to the cleaning agent being dumped into the water became a defining image of the civil rights era. Still, the damage caused by decades of systematic discrimination was done.

“If you look back through history, segregation was one of the things that kept a lot of people out of the sport,” James Washington, aquatics director for the D.C. Department of Parks and Recreation, said. “History changed and we were allowed access, but by then, many had grown to do other sports. They moved to the sports that allowed people of color.”

‘Why are you swimming?’

For McClendon’s part, there was never really another sport. She was introduced to swimming after being diagnosed with scoliosis as a child. McClendon loved that the sport gave her her own space and her own lane, and that how she performed was totally up to her. But most of all, she loved racing, chasing others down in relays and then being rewarded with a prize. She still has the trophy she won as a youngster during a championship meet in her native Puerto Rico.

“My breakout meet,” she joked.

But it wasn’t long before her budding success was met with questions and judgment. She readily recalls an incident when, at just 10 years old, she was confronted by a parent on the pool deck after a series of fast swims.

“Why are you swimming?” the woman asked.

The question puzzled the young athlete.

“What do you mean?”

“Don’t you think you need to go to a basketball court or go do track and field or something?” McClendon, a silver medalist at the 2004 Athens Olympics, recalled her saying. “This was her way of pushing me down in the dirt a little bit.”

From subtle microaggressions to acts of overt racism, such tales remain all too common. Consider what occurred in July at Carter Park Pool in Ft. Lauderdale. According to NBC News, a white woman reportedly demanded that police be called on a Black woman and her son, both members of Diversity in Aquatics, simply because they were talking across pool lanes.

This incident, said Lynch, is just one more example of the very things that have kept Black people from the pool.

“This is a barrier. Why would you want to go there?” she said. “There’s often a feeling of whiteness as property at the pool. This is mine, not yours. You can’t address the disparities if you’re not feeling welcome there to begin with.”

Taking power back

In response, Diversity in Aquatics organized a community swim-in as a means of protest and restorative justice. Word spread on social media, and a social-distanced family reunion of sorts quickly materialized.

“This was a form of healing,” Lynch said. “Their hostility will not take the energy from this pool. This was our way of saying, ‘No, this place is sacred to us. This was built for us. We know this is a diamond for us here, and we’re not going to let people walk us away from this place.’”

Athletes are using their platforms to promote water safety and facilitate change. McClendon has spent the past eight years representing Swim 1922, a partnership between USA Swimming and sorority Sigma Gamma Rho designed to increase participation and decrease drowning rates in the Black community. It’s been a rewarding venture, one that’s enabled her to help scores learn to swim, including an 82-year-old woman who went from resisting the mere idea to floating on her back in less than an hour and wondering why she’d waited so long.

“I hear she’s now doing water Zumba,” McClendon said with a laugh. “I really want to connect with the Black community, instead of just the teams. Let’s go into the places where there isn’t a swim team and figure out why not. This is what I want to do.”

She’s not alone. Since his gold-medal moment alongside Michael Phelps, Garrett Weber-Gale and Jason Lezak in the 400-meter freestyle relay at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Cullen Jones has made it a priority to bring others into the water with him. For him, the fight is personal.

Empowering the next generation

Jones, a two-time Olympian, learned to swim after almost drowning at a water park at age 5. For the past 12 years, he has served as an ambassador for USA Swimming’s “Make a Splash” initiative, a program aimed at promoting water safety in underserved communities. It provides free or reduced-cost lessons through a network of local learn-to-swim programs, offering a critical life skill while removing a financial barrier that can turn some families away from the sport. So far, more than 7.5 million children have learned how to swim through “Make a Splash.”

Jones’ impact on the sport doesn’t end there. After George Floyd was killed while in police custody in Minneapolis, the four-time Olympic medalist joined other Black swimmers in helping USA Swimming craft a message condemning racism while also acknowledging the role the sport has played in fostering discrimination and outlining a path forward.

“We need to keep our mouths open about things that are going on because we are the faces of what USA Swimming is in diversity,” Jones said during a webinar for “Swimmers for Change,” a grassroots movement launched by Neal and Jacob Pebley to bring awareness to Black Lives Matter and combat racism. “We need to make sure that these young people, as they’re coming up, they understand that they can look to us.”

It was that message of inclusivity, belonging and support that McClendon sought to deliver during a recent Zoom call with young swimmers from Miami’s Alper J Swim Club.

“I think it’s important to provide a safe zone for all swimmers,” McClendon told them. “It doesn’t matter what you look like, where you’re from, what you do, what your parents do. You’re in that pool. You have the ability to be whatever you want to be. Don’t let anybody else tell you otherwise.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports