Film reviews round-up: Borg McEnroe, On Body and Soul, In Between, In the Last Days of the City

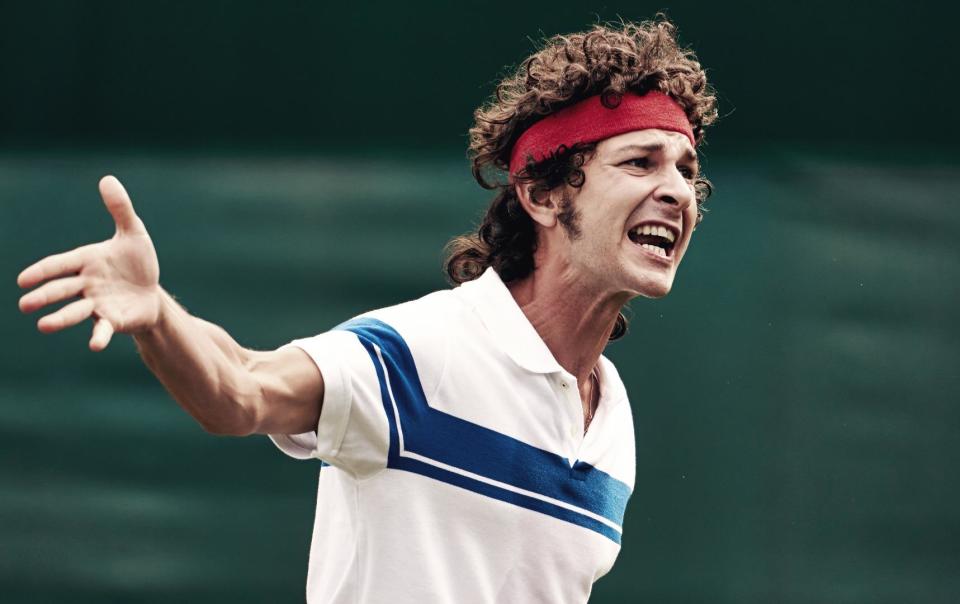

Borg McEnroe

★★★☆☆

Dir: Janus Metz Pedersen, 108 mins, starring: Shia LaBeouf, Sverrir Gudnason, Stellan Skarsgard, Tuva Novotny, David Bamber, Robert Emms, Jane Perry, Scott Arthur, Leo Borg

It’s the “Iceberg” against the “Superbrat” in this curiously undercharged sports biopic. In 1980, the 24-year-old Swedish tennis star, Bjorn Borg, played the younger American, John McEnroe, in a classic five-set match in the Wimbledon singles final. That match is the finale of Janus Metz Pedersen’s film. It isn’t at all clear what the story gains by being dramatised. A documentary could have covered the same ground as well, if not better.

Borg McEnroe is informative and well-acted but also very predictable. It lacks the intensity that its two protagonists, in their very different ways, brought to the court. There isn’t much humour here. The film conspicuously fails to do justice to the New Yorker wit that went alongside McEnroe’s tantrums. Nor, in spite of the presence of playboy Vitas Gerulaitis (Robert Emms) and a brief scene in nightclub Studio 54, is there much sense of the glamour that surrounded top-level tennis in the late Seventies and early Eighties.

In an intelligent and nuanced performance as McEnroe, Shia LaBeouf captures the American’s spikiness and hostility toward officialdom. He shows his character’s self-awareness and faltering attempts to overcome his own obnoxiousness. In one telling moment, his doubles partner and quarterfinal opponent Peter Fleming says to him: “You’ll never be one of the greats because nobody likes you,” and McEnroe, realising the truth in Fleming’s remark, tries to apologise but can’t quite bring it off. LaBeouf, though, doesn’t have McEnroe’s athletic grace or his repartee.

Sverrir Gudnason looks uncannily like Borg and has that inscrutable and impassive quality that so discomfited Borg’s opponents. Borg’s own son, Leo Borg, plays the Swede as a youngster.

A darker telling of the story would surely have portrayed both men as psychopaths. As we see in flashbacks, Borg was famously petulant as a young player. He learned to hide his emotions but his desire to win was just as all-consuming as that of McEnroe. (“They say he’s an iceberg. Really, he’s a volcano,” it is said of him.)

“Tennis uses the language of life,” we’re told at the start of the film as if the tussle between the two players is some primal struggle that will reveal deeper insights about the nature of human competition. In fact, this is just another sports story which ratchets up to a very predictable climax. The 1980 Wimbledon final itself is recreated in an utterly formulaic fashion. Close-ups of the players are intercut with subliminal shots of the “real” match and very arch commentary from Swedish, American and British TV journalists as strident music plays on the soundtrack.

The film begins with the build-up to the 1980 Wimbledon championships. Borg is in Monaco, where he lives as quietly as he can, ducking celebrity autograph hunters. McEnroe is on the chat-show circuit. The tabloids are branding him as potentially Borg’s worst nightmare.

Ronnie Sandahl’s screenplay lobs in flashbacks in routine fashion. Borg is from very humble circumstances. “Tennis is not a sport suited to all levels of society,” the snobbish Swedish officials tell his mother when his bad behaviour as a youngster is getting out of hand. As a boy – and then as an adult – he is shown as being an absolute perfectionist. If the upholstery in a courtesy car isn’t to his liking or a TV crew is filming his childhood haunts in what he considers to be an inaccurate way, he will complain. His coach, the wily old former Wimbledon quarter-finalist Lennart Bergelin (Stellan Skarsgard in a skull cap), is the only one who knows how to manage him. Skarsgard is good value as the Burgess Meredith type to Borg’s Rocky. He can see that the young player has a backhand like an ice hockey “slapshot” and spots the potential the other coaches miss.

McEnroe, meanwhile, is growing up in New York with “tiger” parents who push him in maths as much as tennis. (His party piece is to solve fiendishly complicated arithmetic puzzles.)

This is a Swedish-made film (albeit with a Danish director) and the emphasis is far more on Borg than it is on McEnroe. The final is acclaimed by the Scandinavian media as the “greatest moment in the history of Swedish sports”. The filmmakers don’t dissent from that view. On one level, this is a buddy movie, even a love story. McEnroe is the worthy opponent that Borg needs to prove his own greatness. By the final reel, when the two players embrace, Borg certainly seems more interested in his adversary than in his long-suffering fiancée, Mariana (Tuva Novotny).

On Body and Soul

★★★★☆

Dir: Ildiko Enyedi, 116 mins, starring: Geza Morcsanyi, Alexandra Borbely, Zoltan Schneider, Ervin Nagy, Tamas Jordan, Zsuzsa Jaro

In the 1950s, the great American screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky wrote Marty, a TV play later made into a film about a lonely butcher in the Bronx who meets an equally solitary woman. They’re such vulnerable and fragile souls that getting together is an epic quest.

Surrealistic Hungarian drama On Body And Soul, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, is a long way removed from the New York social realism of Marty but its two main characters are very similar to the protagonists in Chayefsky’s drama. There’s Endre (Geza Morcsanyi), the very quietly spoken finance director working in a slaughterhouse, and then there is Maria (Alexandra Borbely), the new quality controller. She is deeply repressed, with a horror at the very idea of human contact.

Director Ildiko Enyedi comes at a familiar idea in an original and sometimes startling way. She begins with lyrical imagery of a stag and a deer in a snow-covered forest. That makes a complete contrast with the very visceral, bloody and matter-of-fact footage that follows of cattle being slaughtered and chopped up in the abattoir. Endre’s first attempts at talking to Maria are gauche in the extreme. He tries and fails to engage her by discussing the range of salads available at the slaughterhouse cafeteria. In the safety of her own apartment, she recreates their conversation using the salt and pepper pots. What really draws Endre and Maria together is the fact that they are having identical dreams. That’s where the deer in the forest come in.

On Body And Soul is very hard to classify. It resists being labelled a Freudian drama. Nor is it a conventional love story. It has moments of very deadpan humour but they sit next to scenes of wrist-slitting despair. The film, though, is beautifully played by its two leads and has a wonderfully barbed and unsettling quality that you will never find in any Hollywood romcom.

In Between

★★★☆☆

Dir: Maysaloun Hamoud, 101 mins, starring: Mouna Hawa, Sana Jammelieh, Shaden Kanboura, Mahmud Shalaby, Henry Andrawes, Ashlam Canaan

Modernity and tradition clash headlong in Maysaloun Hamoud’s very likeable drama about three female flatmates in Tel Aviv. They’re all chafing against the restrictions placed on them by their menfolk, whether their fathers or fiancés. The most outspoken of the three Arab-Israelis is Layla (Mouna Hawa), a chain-smoking lawyer whose handsome new boyfriend is ashamed to be seen with her in front of his family. Then there is DJ Salma (Sana Jammelieh), the apple of her father’s eye until he discovers she is a lesbian. The newest flatmate is Nour (Shaden Kanboura), a strict Muslim who is studying at the local university. She has a very boorish boyfriend who wants her to stay at home and follow his orders in everything. Under the influence of Salma and Layla, she refuses to be browbeaten by him.

Writer-director Hamoud shows the women enjoying themselves, drinking and partying. This isn’t just about selfish pleasure and hedonism. It’s a way of expressing their independence and defying the patriarchal society in which they are all caught. They endure some grim moments – sexual assault, bullying and social humiliation – but the film celebrates their resilience and irrepressible good humour in the face of the priggish menfolk who surround them.

In the Last Days of the City

★★★☆☆

Dir: Tamer El Said, 117 mins, starring: Khalid Abdalla, Laila Samy

In The Last Days Of The City is provoking controversy in Egypt. It was “pulled” from the Cairo Festival late last year and hasn’t yet been released in the country. You can see why the authorities are so uncomfortable. This isn’t so much a political polemic as a meditative lament. Largely shot between late 2008 and 2011, straddling the lines between fiction and documentary, it follows a filmmaker Khaled (Khalid Abdalla) as he tries to sort out problems in his personal and professional life. His mother is hospital-bound. He needs to find an apartment. He is struggling to make his next film. His woes, though, are nothing to those of the city he loves.

It’s the eve of the Arab Spring and Cairo is in a state of ferment. Protesters are on the streets. Khaled witnesses incidents of brutality – men assaulting women, protesters being arrested and bundled away by the police. As the unrest rises, the radio announcers blandly announce details of the national football team’s latest triumphs or decry the Muslim Brotherhood. Some of his close filmmaker friends have already left the city and are living in exile in Berlin or Baghdad.

Director Tamer El Said shoots in a fluid way as if this is a poetic travelogue shot by a local resident. The film benefits from Khalid Abdalla’s soulful performance as the director wandering through his old haunts. He is a melancholy presence, a little like one of those angels over Berlin in Wim Wenders’s Wings Of Desire. The film is already a period piece. Former dictator Mubarak is now long gone. The knowledge of the upheavals that Egypt has experienced in the intervening years only adds to the poignancy here. Things have gotten worse, not better.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports