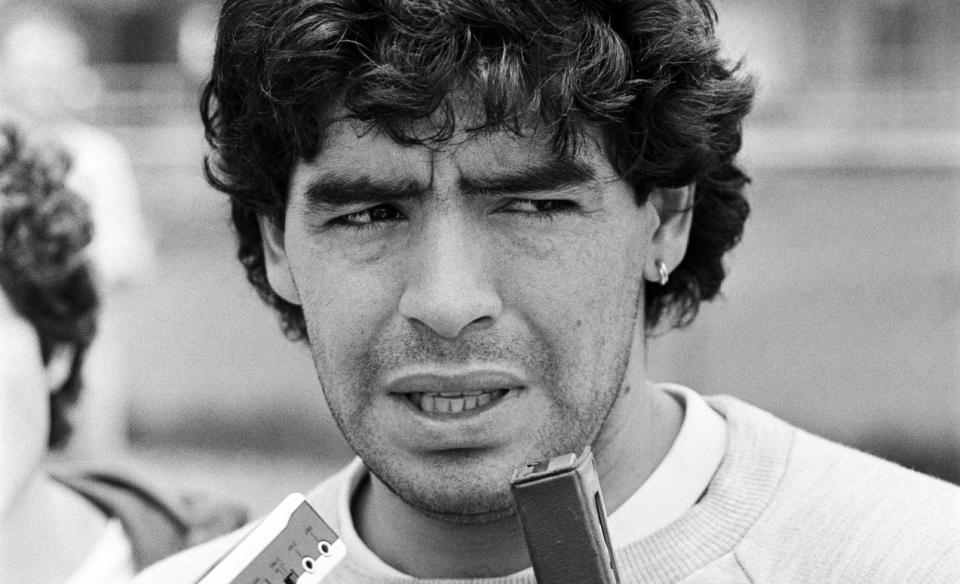

Diego Maradona lived a life too large to capture

The duality in Diego Maradona’s outsized life was perhaps laid out clearest within his most famous game. In the quarterfinal at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, against Argentina’s hated rivals England, just four years after they fought the brief Falklands War, Maradona set up an attack that appeared to be going nowhere. But England midfielder Steve Hodge clumsily shanked the ball back between Maradona and English goalkeeper Peter Shilton.

Maradona, standing a stocky 5-foot-5, somehow dinked the ball over the 6-foot Shilton, who was permitted to use his hands, to give the Argentines the lead.

Replays showed that Maradona had used his fist to punch the ball into the net. The referees hadn’t noticed. The goal stood.

Four minutes later, the 25-year-old from the slums of Buenos Aires, who had been the last player cut from Argentina’s 1978 World Cup-winning team when he was just 17, dribbled through just about the entire English team to score and win the game — and keep his team on track to win the World Cup.

One of the most iconic goals in #WorldCup history.#OnThisDay in 1986, a moment of pure genius from 🇦🇷 Diego Maradona✨ pic.twitter.com/iVR9upkgYW

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) June 22, 2019

The first goal came to be known as the “Hand of God.”

In his description of the second goal, a tearful Argentine play-by-play announcer Victor Hugo Morales famously asked Maradona what planet he had come from.

Maradona inspired and Maradona defied the rules.

Maradona died on Wednesday, less than a month after his 60th birthday, likely from complications after a blood clot in his brain was treated surgically.

To some he was God. Or his hand was Godly, at least. There is even a Church of Maradona in Argentina with a congregation of his disciples, still going strong 23 years after he last kicked a ball professionally for his beloved Boca Juniors, the club that launched him to stardom. To others, he was otherworldly.

Because Maradona contained multitudes. He was one of the greatest players to ever play soccer, utterly dominating Serie A with unglamorous Napoli in the late 1980s in the prime of a long but tumultuous career, beset by conflict. He was also one of its biggest lightning rods.

For his divine-adjacent brilliance, for his uncatchable dribbles and irrepressible attacking thrust in the face of brutal tackles by unchecked defenses, Maradona also had his demons. He was a hedonist, whose excesses may have slowed his career and certainly caught up to him later in his life. He was a habitual drug user and was kicked out of the 1994 World Cup for doping. He was all too cozy with the Camorra crime organization when he lived in Naples.

He was a philanderer and took decades to acknowledge an illegitimate child. He owed the Italian government tens of millions of euros in back taxes that he never did get around to repaying. He could be racist. There’s footage of him hitting a girlfriend. He consorted with dictators like Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez.

But for all the baggage, Maradona retained an undeniable charm. His talent was so outrageous and his play so joyful as to be completely mesmerizing.

There is endless video of him dancing, even when he was old and overweight and barely able to move — utterly unrecognizable from the forward who could be kicked but somehow never caught.

Maradona won the Argentine league with Boca and twice conquered Serie A with Napoli, also lifting the UEFA Cup with the club whom he lifted out of mediocrity. He brought Argentina to a second World Cup final in 1990. He scored 259 league goals for his clubs, even as he usually shouldered the dual burdens of being creator and finisher, while also taking the brunt of the punishment from opponents. Perhaps a lifestyle more devoted to his craft might have yielded more. But that wasn’t Maradona’s way. He played the way he lived: with abandon.

Such was his stature that throughout his post-playing managerial career, which was littered with failures, he was nonetheless treated like a deity. In his final job, in charge of Gimnasia de La Plata of the Argentina Primera Division, an opposing team presented him with a throne from which to manage the game along the sideline.

He forever loomed over Argentine soccer, his opinions carrying the heft of a head-of-state, his playing legacy casting an immeasurably long shadow over every subsequent attacking prodigy to emerge from the talent-rich nation — one that even the all-conquering Lionel Messi has never entirely escaped.

Maradona was the kind of outsized character who, warts and all, can scarcely be sketched out in a retrospective of his life such as this one. He simply did too many remarkable things. The boy who rose from destitute poverty and supported his family from the age of 15 lived a life too large to capture.

Leander Schaerlaeckens is a Yahoo Sports soccer columnist and a sports communication lecturer at Marist College. Follow him on Twitter @LeanderAlphabet.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports