You should care more about the ‘Maus’ book ban than any Joe Rogan controversy. Here's why

You’re not paranoid. They really are coming for books.

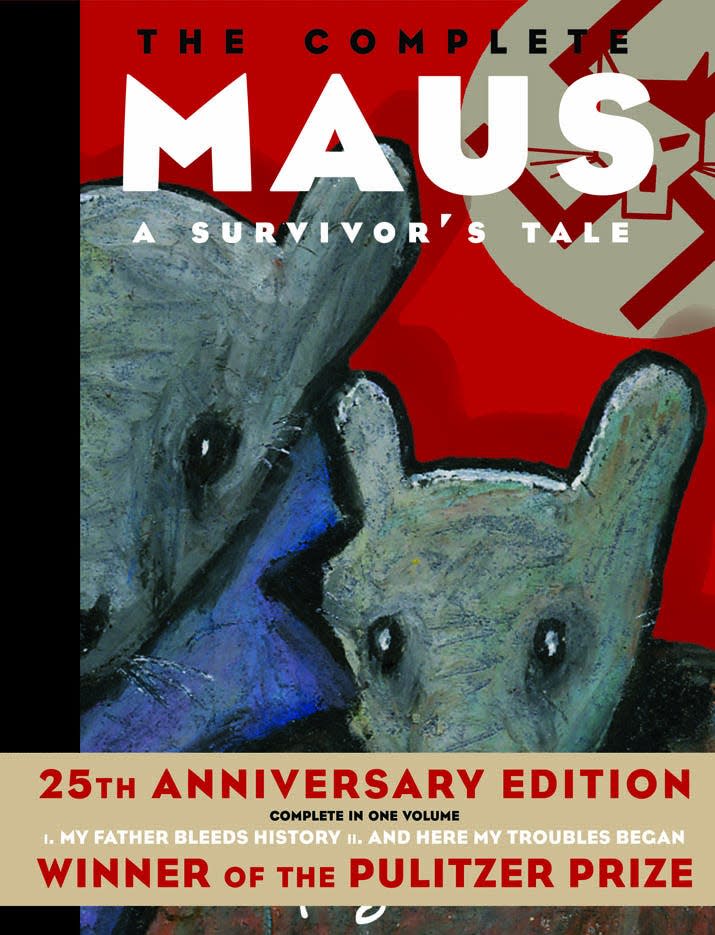

The onslaught of book banning headlines has been staggering. In Tennessee, the McMinn County School Board voted in January to ban Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel “Maus,” which tells the story of comic artist Art Spiegelman's Jewish parents surviving the Holocaust.

In Virginia, Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin, who took office last month, ran in part on the promise that he would give parents more of a say in their children’s education. One of his campaign ads last fall featured a mom who didn’t want her son to read Nobel Laureate author Toni Morrison’s "Beloved," a book about haunted former slaves set after the Civil War. Morrison’s work has also been challenged in Missouri, where the Wentzville School board voted to pull "The Bluest Eye" from its schools' libraries.

Book banning:Here's it does to students.

This book banning wave isn't just affecting schools. In Mississippi, Ridgeland Mayor Gene McGee is withholding $110,000 from his city's library because LGBTQ books are on the shelves, The Associated Press reports.

It really is as bad as it looks, says Patty Wong, president of the American Library Association. “The numbers have increased quite a bit,” she says.

The ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom tracks book banning efforts across the country, and the numbers are striking. Between September and November last year, the ALA received reports of more than 330 unique book banning cases. Challenge totals in 2021 more than doubled the number of reports from 2020 and likely outpaced 2019 figures (complete 2021 numbers will be released April 4).

The volume and types of books being challenged worry Wong. “Books really are meant to reach across boundaries and build connections between readers. Reading, especially books that extend beyond our own experiences, expands our worldview,” Wong says. “That whole worldview approach is being challenged.”

Why banning books is so dangerous

This is hardly America's first book banning rodeo. In the 1982 Supreme Court case Island Trees School District v. Pico, a group of New York students filed a lawsuit against their school board, claiming a violation of First Amendment rights when it removed objectionable books from its schools’ libraries, including Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” and Richard Wright’s “Black Boy.”

The court was split in its decision, but Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote for the plurality opinion that "local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.’ Such purposes stand inescapably condemned by our precedents.”

And yet that’s precisely what’s happening in schools across the country, according to Lara Schwartz, founding director of the Project on Civil Discourse at American University. She’s a lawyer by training who built her career in civil rights advocacy and particularly First Amendment and free speech issues. To say she’s concerned by the increase in efforts to challenged books would be an understatement.

“This is enormously, enormously, five-alarm-fire concerning,” Schwartz says. “This is a deluge of state and local legislation efforts to prevent students from learning, to prevent teachers from being able to discuss and explore some of the most important issues of the day.”

It’s not just constitutional scholars and librarians sounding the alarm. Teachers on the front lines of this latest culture war are expressing deep concern about the types of books that are being targeted and what it means for their students.

Bree Rolfe, a writer and educator who teaches creative writing and 10th grade English at James Bowie High School in Austin, Texas, is particularly worried about the types of books that are being challenged: books by Black authors that deal with racial identity and racism; books by Jewish authors about the Holocaust; and books featuring LGBTQ characters.

“That makes me and my students feel very unsafe,” Rolfe says. “When you’re young and you go to books to see yourself and to see people like you, to have that be banned and have that be something people are fighting for across the nation, banning who you are? That to me is very unsafe. And very scary.”

Reading books builds empathy, Rolfe says. “It’s very important to see perspectives and experiences we haven’t experienced and never will,” Rolfe says. “If we can build empathy for characters in literature, we can translate that into the real world.”

Schwartz says human progress depends on exposure to challenging ideas. “This is why we educate, this is why we learn, this is why hopefully people open your newspaper,” she says. “Human progress depends upon our capacity to find out that we’ve been wrong. Every bit of human progress has come from exposure to new ideas that enables us to see what we believed before was incomplete in some way.”

They're trying to ban 'Maus': Why you should read it and these 30 other challenged books

Many of the conservative arguments for banning specific books focus on material they deem inappropriate for students. In the case of "Maus," the Tennessee school board cited in a statement "unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide."

"Taken as a whole, the Board felt this work was simply too adult-oriented for use in our schools," part of the statement read.

Rolfe believes those arguments underestimate kids and their capacity to process difficult topics. "I think kids are resilient and if you have a conversation with them and you help them process the literature, then it's a safe environment," Rolfe says. "One of the reasons you read some of these tough books at school is because you have an adult there and a safe space in a classroom full of people to process what you're reading."

The difference between ‘Maus’ and Joe Rogan

In the weeks since the banning of “Maus” drew national outrage, the culture war has metastasized and largely moved on. Now the free-speech magnifying glass is largely centered on comedian and podcaster Joe Rogan and his podcast, "The Joe Rogan Experience."

Rogan’s podcast initially came under fire for its spread and amplification of COVID-19 misinformation. Rogan, who tested positive for the coronavirus in September, has been openly critical of safety measures against the virus and has downplayed the need for mass vaccines on his podcast. With the criticism came increased scrutiny of Spotify, the music streaming service that reportedly signed a deal with Rogan worth more than $100 million.

Artists including Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Nils Lofgren have responded by requesting their music be removed from Spotify.

The controversy deepened over the weekend after a six-minute video compilation surfaced showing Rogan using a racial slur in numerous podcast episodes. Spotify responded by removing a number of offending episodes, but CEO Daniel Ek said in a message to employees released Sunday that the company would not part ways with Rogan.

“We should have clear lines around content and take action when they are crossed, but canceling voices is a slippery slope. Looking at the issue more broadly, it’s critical thinking and open debate that powers real and necessary progress,” Ek wrote. A number of comedians, including Whitney Cummings and Jon Stewart, have spoken out in support of Rogan’s right to his podcast.

Joe Rogan: Apologizes for 'regretful,' 'shameful' use of racial slur after clips circulate

So, how is the call for Spotify to drop Rogan, which largely comes from liberal circles, different from largely conservative legislators' actions to remove books from school libraries and curricula? The first centers on private citizens exercising their First Amendment rights and the latter on the government violating First Amendment rights.

The First Amendment binds governments and not companies, Schwartz says, and Spotify is not the government. Artists pulling their music from Spotify in protest are exercising their speech rights, as are consumers engaging in an economic boycott by canceling Spotify subscriptions.

Book bans, Schwartz says, are by design a form of discrimination by the government. “They’re designed to ensure that kids don’t get access to multiple ideas or viewpoints,” she says. The books targeted aren’t being banned because they’re false or contain misinformation, but are “books the banners perceive to present society in a light they don’t want it presented.”

That is also Rolfe’s fear as an educator. The widespread targeting of books by and about marginalized communities has her worried for her students.

“It’s hugely upsetting. It’s scary,” Rolfe says. “In some ways, it’s almost as if some of the dystopian books we teach have been coming to life.”

To report book banning efforts in your community, contact the ALA at 1-800-545-2433 x4226 or email oif@ala.org. You can also file a report online at ala.org. All reports are anonymous.

Contributing: Mike Snider; The Associated Press

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Banning ‘Maus’ book matters more than any Joe Rogan controversy

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports