Black 30 and under: Young Miamians talk about where they feel at home in their blackness

Spend any amount of time with Loralei Gonzalez and Nadia De La Mora and it’s clear why they’re friends.

They helped create Black Student Unions at their respective South Florida high schools. They have similar majors. And they finish each other’s sentences.

Both aren’t even old enough to buy a drink yet. Gonzalez, 19, and De La Mora, 19, have already lived through a global pandemic, an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol and arguably the largest Civil Rights movement in American history. At Florida International University, which both attend, the two friends hoped to make sense of it all. What they discovered, however, is the importance of community.

“No one likes to have uncomfortable conversations,” Gonzalez, a freshman, said.

“I don’t have to walk on egg shells to have this conversation which is how I feel when I talk to other people who aren’t Black because I’m making them uncomfortable,” De La Mora, a sophomore, said.

Gonzalez added: “I don’t have the privilege to be uncomfortable.”

Black spaces have become a critical part of survival in America. Free from oppression and the white gaze, these spaces — whether a physical location or around a group of people — allow Black Americans to shed their masks and truly be themselves. Historically, the racism that ran rampant in Miami-Dade County forced the creation of neighborhoods like Overtown and Richmond Heights while cities like Miami Garden were created as an act of self-determination. And as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis continues his purported “war on woke,” something critics deem an attempt “to exterminate Black history,” these spaces have never been more important.

“It wasn’t until I started hanging out with people who are a little more like me or grew up like me that I started feeling comfortable being myself and being totally into my Blackness,” De La Mora said, later adding “I love being Black so much… We really had to make something out of nothing.”

Wanting to build that community is also what prompted Francesca Morgan, 30, and her friends to start the Slice Girls, a tennis club composed primarily of Black women.

“We created our safe space here,” Morgan said of Allapattah’s Moore Park, where the club meets bimonthly.

Born and raised in North Miami, Morgan grew up surrounded by Black people. What she didn’t see, however, was a lot of tennis players who looked like her. That is, until the domination of Venus and Serena Williams. Now, Morgan wants to ensure the next generation knows that tennis welcomes everybody.

Moore Park is “in a Black neighborhood, the coach here is Black and children are not exposed to the sport of tennis as they are many other sports,” Morgan explained. “So when they see Black people playing on the court, they feel more represented and they feel they can easily tap into the sport.”

As Morgan referenced, places like Moore Park also allow younger generations to observe adults. For many kids, a trip to the park is their first taste of freedom. No parents. No grandparents. No rules (except curfew). Just friends, fun and, in Desmond Jones’ case, football.

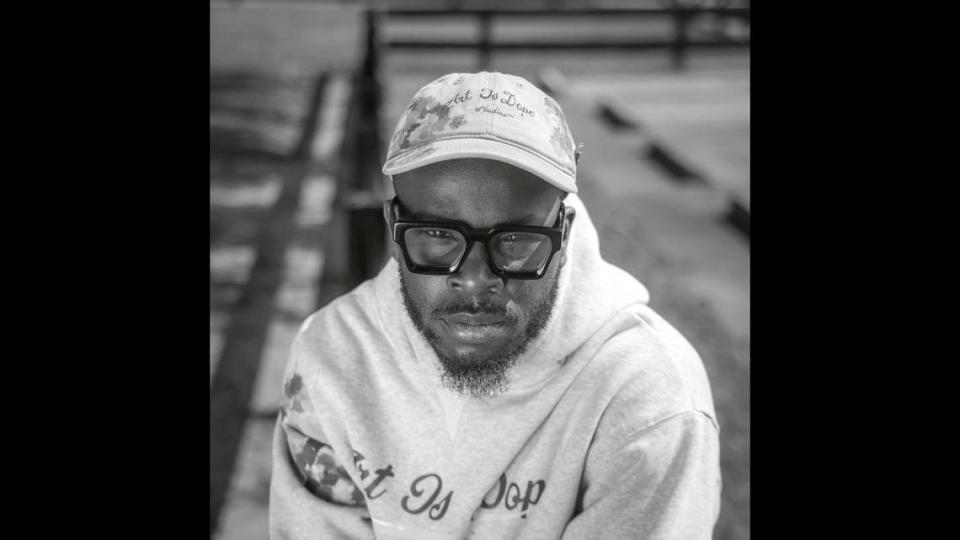

“This is where I grew up,” Jones, an artist and fashion designer behind the brand Art is Dope, said of Carol City Park. “I’d probably be playing football” if art didn’t work out.

Located in Miami Gardens, Florida’s largest primarily Black city, Carol City Park opened up Jones’ mind. He saw the good. He saw the bad. He saw the ugly. That combination, however, ingrained in him the importance of hard work. Eventually, his diligence paid off with Jones now having designed clothes for Miami Dolphins receiver Tyreke Hill, collaborated with Luc Belaire and hosted a pop-up inside the Nordstrom at Aventura Mall.

“Hustling is definitely in Carol City,” Jones said. “I remember going to Carol Mart, Rick Ross ‘hustling, hustling, hustling’ — that inspired me as a jit. It made me be like, ‘Dang, let me go do something.’”

For Mahlik Hunt, the 30-year-old owner of executive protection company Darkside Protection, the city of Miami Gardens itself is his safe space. He too played football in the city’s parks. Frequented the Carol Mart. Bought his first pair of shoes at the footlocker in Dolphin Plaza.

“Being in different countries, different regions of the world and coming back here, I just feel whole,” Hunt, 30, said.

An entrepreneur himself, Hunt understands the ups and downs of being your own boss. When asked where he feels the most comfortable, his answer was simple: shoe shopping at Achille Apparel, a store owned by his longtime friend that’s located a few doors down from the Footlocker where he selected his first pair shoes.

“Growing up, I couldn’t always afford the newest shoes,” said Hunt, a smile slowly forming on his lips. “Now, I’m going in and buying all these different types of shoes that I would’ve never been able to purchase as a kid.”

Being able to buy from a friend whose business lives in the city where he grew up makes it all the more worthwhile.

“We want to see the elevation of Black excellence,” Hunt said.

During Black History Month, the Miami Herald is conversing with Black Miamians 30 and under to learn about how they feel on a range of issues. Meet some of them on the Miami Herald Instagram, where we will post photos and interviews each week.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports