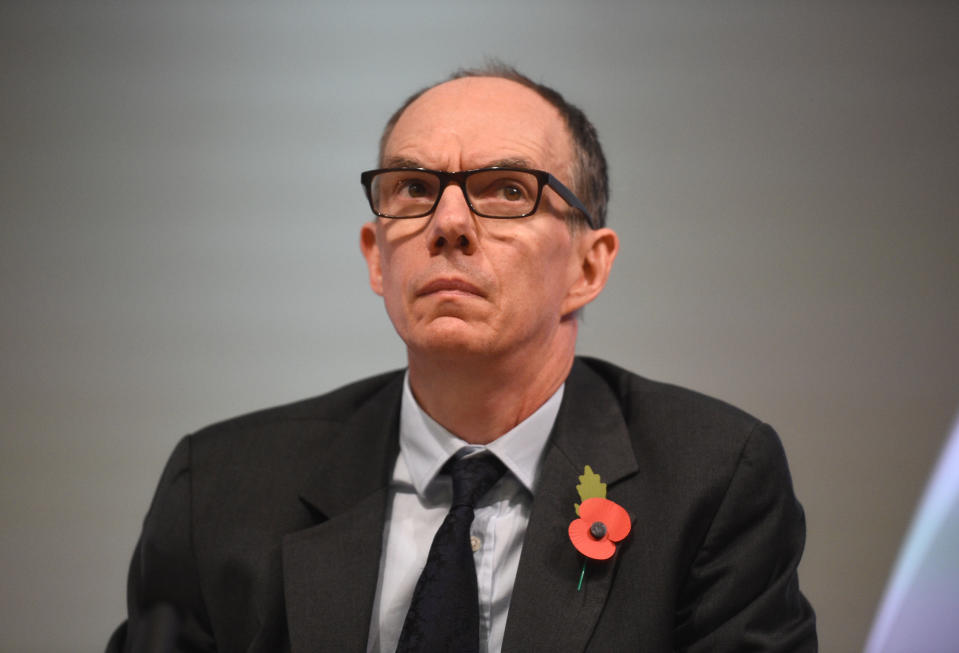

'Record level' of uncertainty for UK economy, warns Bank of England governor

The UK economy is facing a “record level” of uncertainty about its future, the governor of the Bank of England warned on Wednesday, with a significant risk that growth will be far weaker than currently forecast.

Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey told MPs that forecasts drawn up in August were done in the face of huge uncertainty caused by the continued battle against COVID-19, structural changes in the economy, and Brexit trade talks.

Bailey said the Monetary Policy Committee’s measure of uncertainty stood at its highest level in history during the August meeting.

READ MORE: Bank of England: UK economy to have biggest annual decline in 100 years

Last month, Threadneedle Street forecast that UK GDP would fall by 9.5% this year, its sharpest slump in over 100 years. The central bank said long-term growth was likely to be 1.5 percentage points below pre-COVID forecasts, reflecting expectations that the pandemic will permanently reduce economic potential through “scarring.”

Bailey told MPs on Wednesday that risks to these forecasts were skewed to the downside, meaning worse-than-expected growth was far more likely than better-than-expected.

“There was broad agreement on two things,” Bailey told the Treasury Select Committee. “One, there’s a very high degree of uncertainty… and there’s a very big downside skew.”

Ongoing features of the pandemic — such as continued local lockdowns and the risk of a second COVID-19 spike this winter — were not factored into the Bank of England’s forecasts, raising the possibility of future downgrades if these risks become reality.

“We didn’t make any assumptions about vaccines, we didn’t make any assumptions about the precise pattern of COVID going forwards because, frankly, we don’t know,” Bailey told MPs.

READ MORE: Coronavirus: UK manufacturing output grows at fastest pace since 2014

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee also avoided making any predictions on “structural issues” accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis, such as the shift of retail online or the decline of city centre offices.

“How much structural change will there be in the economy as a consequence of the shock that has happened?” Bailey said. “How is that going to manifest itself? That’s the thing that can lead to what we call scarring.”

Another risk is that changing behaviours could damage the economy if people remain reluctant to do things like return to offices, visit attractions, or go to shops.

“In the short run, clearly there’s a lot of uncertainty and different views around the question of how much what we call sort of natural caution enters into the behaviour of people in the economy,” Bailey said.

Finally, the looming outcome of Brexit trade negotiations could also cause disruption. Bailey said the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee would focus more on Brexit at its November meeting.

Sir Dave Ramsden, deputy governor for markets and banking, told MPs the 1.5% hit to long-term GDP was “a good starting point” but added: “For me all the risks are that that number will be greater than 1.5%.”

Ramsden raised the issue of the structural shift from office work to remote working.

“Will that add up to a less productive or a more productive economy? That’s an open question,” he told MPs.

“We didn’t really draw any conclusions on that at this stage. But that’s the kind of mechanism that you’d want to consider to ask yourself whether there might be more permanent scarring on productivity alongside the labour market.

“Unless the adjustment is very quick and happens quite easily, the chances are the scarring effects over time will be larger than that.”

READ MORE: Central banks can only play 'modest' role in tackling coronavirus inequality

Given the heightened uncertainty and skew to the downside, Bailey said the Bank of England would be more cautious than usual when normalising its highly accommodative monetary policy.

“We’re going to need more than normal evidence and assurance that the economy is on track and therefore inflation is on track to return to target before we act,” he said.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports