15-Year-Old Katie Ledecky Felt ‘Zero-Pressure’ at Her First Olympics—And Left a Gold Medalist

Heinz Kluetmeier/Robert Beck/karomlopburi/Getty Images/Spencer Blake/Amanda K Bailey

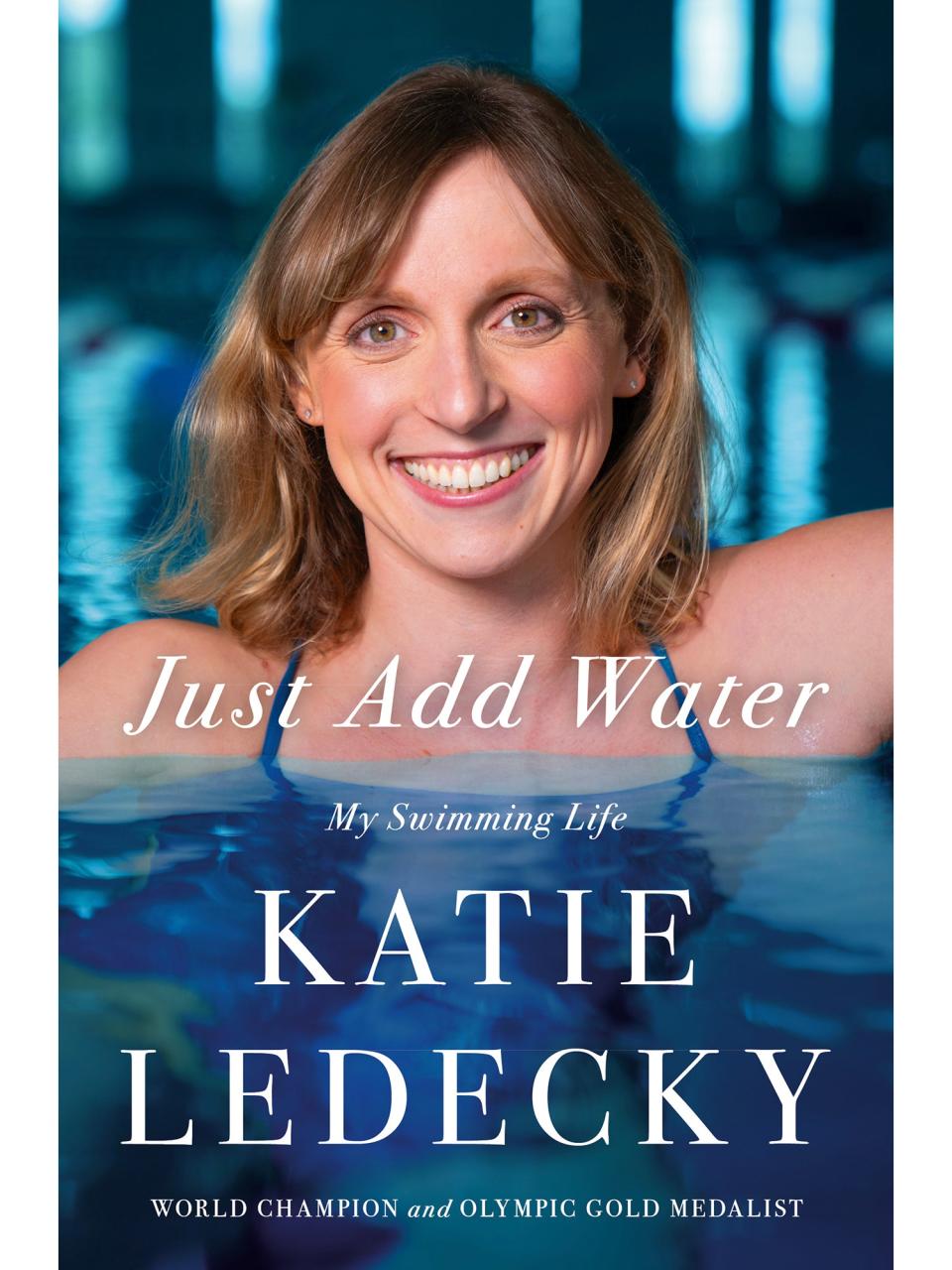

At just 15 years old, swimmer Katie Ledecky earned her first gold medal at the 2012 London Olympics. Now, at 27, she has seven Olympic gold medals and 21 World Championship titles under her belt, cementing her name in sports history. In this exclusive excerpt of her new memoir, Just Add Water: My Swimming Life, out today, Ledecky looks back at her earliest days in the sport and details how her win in London took everyone but her by surprise.

I was six the first time I met Michael Phelps. It was the summer of 2003, and my older brother (then nine) and I decided to wait outside the Eppley Recreation Center Natatorium at the University of Maryland for a chance to interact with one of the most prolific young swimmers in the country.

Our family had been at the pool all day, watching some of the biggest names in American swimming competing at the U.S. National Championship meet. Even though I was a young girl and a novice swimmer, I’d noticed Phelps and was captivated by his presence in the water. He was only eighteen then, another Maryland native, and a swimmer who was busy redefining what was possible in competitive swimming. Two weeks before, at the 2003 World Championships in Barcelona, Phelps had won four gold medals and two silvers. He’d also set three world records—in the 200-meter butterfly, 200-meter individual medley, and 400-meter individual medley. (Phelps would go on to earn twenty-eight Olympic medals, twenty-three of them gold.)

My brother and I stood in the parking lot outside the back door. Sweating. For hours. Eventually, Phelps emerged, alone, no coaches, no entourage. He noticed the line of fans waiting and ambled over in that trademark chill way of his. When he got to me, he bent down and signed a swim cap I’d been clutching in my hand. I can’t remember if I said anything. I’m sure I wouldn’t have known what to say. I do know I smiled so hard I felt it in my jaw.

Swimming is a small world, and swimmers tend to stay swimmers for life. The sport is a little like the Hotel California: You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave. Nine years after I met Michael Phelps in the parking lot as a guileless fan, I was stepping onto the blocks at the 2012 London Summer Olympics, competing alongside him as part of Team USA. In that brief span of time, I evolved from admiring observer to one of the gang. To say that experience was surreal is to do a disservice to the word.

Being at any Olympics is a wild experience. Being a teenager at the Olympics feels like you’ve been transported into a different world. And I wasn’t just the youngest American swimmer—I was the baby of the entire 530-athlete USA delegation.

Prior to London, we had training camp in Knoxville, Tennessee, before traveling to Vichy, France, to adjust to the five-hour difference from Eastern to British time. I was in disbelief early on in Knoxville, when I had the opportunity to swim a practice with swimmers like Phelps, Tyler Clary, Connor Jaeger, Allison Schmitt, and Andrew Gemmell. We were doing a set where we were supposed to hit specific times for different distances. I was not only meeting the times I was being asked to meet but surpassing them. I got through the set with flying colors, until the end—when I hit a wall and tanked. Frank Busch, who was the national team director, pulled me aside and said, “Katie, just do the times, you don’t have to go any faster.”

The truth was that I was keyed up to be swimming with people like Michael and Allison, who were heroes to me. Who wouldn’t be? Besides, I believed I had something to prove. Who was I? A wide-eyed kid from Bethesda. I didn’t even have a driver’s license yet.

A big part of my Olympic journey was coming to terms with my place on Team USA. I was so quiet during the initial days of camp that breaststroker and team captain Brendan Hansen was worried about me. He said he was concerned about whether I was fitting in and feeling comfortable with the rest of the team. He was kind of right. I was away from home, a Catholic schoolgirl among seasoned young adults with no shared experience to speak of outside the pool. I knew literally nothing about what to expect in training camp, to say nothing of the Olympic Games. I remember getting all my racing suits and caps with the flags on them, taking a picture, and thinking, Why am I getting twenty white caps and twenty black caps for a maximum of two races?

Brendan asked if I could join him to chat over a breakfast of eggs and toast. He took the time to check in with me, which was kind of him. He let me know I wasn’t on my own, even if it sometimes felt that way. Everyone feels out of their depth around the Olympics. It’s the big leagues. Nerves and discombobulation are the order of the day.

Thanks to that talk, I calmed down. I began to ease into my surroundings. I learned about the caps. (American swimmers race in white caps in the prelims and semifinals. The black caps are for the finals. You get plenty in case they rip, and they are fun to share with family and friends post-competition.) I clued into the other Olympic rites and rituals. I loosened up. So much so that by the end of camp, as part of another tradition, I didn’t hesitate when asked to imitate a teammate as part of the “rookie skits.” I got assigned Tyler Clary in my group’s skit, and I did such an uncanny impression that the whole room was in stitches. They hadn’t known I had it in me.

Ridiculous as it sounds, that off-the-cuff imitation freed me from my protective shell. After that, I was fully in the mix of the team. I recall sitting at the end of a long table with a bunch of the swimmers, right next to Michael Phelps, who was telling—well, let’s call them colorful stories from his college days in Ann Arbor. He’d forgotten I was there, and when he turned and spotted me at the end of a particularly sensational anecdote, he blanched.

“Katie, I’m so sorry,” he said. “I apologize. You shouldn’t have to hear all that.” I smiled, told him I didn’t mind. I may have been inexperienced and somewhat sheltered, but I wasn’t a complete shut-in. It would take more than Michael Phelps telling a typical college story to shock me.

As I headed into the final camp days in France, any prior awkwardness had all but evaporated, and I was assured enough to make the most of my adventure. My roommate, Lia Neal (who was sixteen at the time), and I connected as newbies around the same age. We had a lot of innocent fun, like scrounging in Vichy for Nutella at two in the morning. How does one ask for Nutella in France? Lia had taken Spanish and Chinese; I had taken French at Little Flower. But the only French phrase I could recall in the middle of the night was: En Anglais? We managed to work it out, procuring Nutella and laughing ourselves silly in the process.

By then I’d realized that Ryan (Lochte), Matt (Grevers), Missy (Franklin), Allison (Schmitt), Rebecca (Soni), and, of course, Michael, whose autograph I had waited for in the parking lot all those years ago, were not distant stars out of reach in the swimming firmament. That I was not just with them, I was one of them. I felt I truly belonged.

This sense of belonging culminated in the filming of a viral “Call Me Maybe” video, a montage of vérité footage of Team USA lip-syncing to Carly Rae Jepsen’s pop hit. We weren’t Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez, but our take was charming in its own right, and people loved getting to see our goofy side. The video was a sensation, netting eighteen million views.

The whole idea came to be when a few of the girls on the team started filming us at practice around 2012, collecting mini clips of us pretending to call someone on the phone, mouthing the lyrics, or dancing underwater. No one knew it was going to be a big thing, so we were all unguarded and hamming it up. Every day at training camp, they shot a bit more. Then, during our charter flight from Vichy to London, we filmed the choreographed dance scene. I wasn’t a huge part of the final cut, but I am in the background in a few shots, grooving along.

When the video dropped, we were giddy, watching the views and likes tick up and up. We knew it was cute, but we hadn’t thought the whole world would champion it the way they did. The video humanized us athletes in an organic way, the opposite of those glossy, super-produced network packages you see every Olympic season. This was a love letter from Team USA directly to the fans, and the fans embraced it wholeheartedly. It also served as a reminder to me of how many people were paying attention to what we—even me, a fifteen-year-old kid—were doing in and out of the pool.

On July 27, 2012, we arrived in London. When I got to the Olympic Village, I was in awe of the athletes I was rubbing shoulders with in person for the first time. Around every corner was a competitor who was the best at their sport, all the international pros and veterans I’d marveled at on TV or at fields and stadiums. Boom! Like magic, I was standing next to a gold medalist in line at the omelet bar.

I pinched myself every day. The opening ceremony parade was giant, and I got to walk with the USA delegation. Most swimmers don’t get that chance because of the schedule. The ceremony is always on a Friday night, lasting four hours and ending well after midnight. The swim meet commences the next morning, making it all but impossible for swimmers to take part in the ceremony. The coaches advise you not to go because it is miles of walking and could interfere with your performance. In Rio in 2016, for instance, after Michael Phelps led the U.S. team into the stadium, he was immediately whisked away.

In London, I got lucky. The heats of the women’s 800 free weren’t scheduled until day six. I was able to fully immerse myself in the festivities, dressed head to toe in my Ralph Lauren Team USA–issued uniform of navy blazer, beret, and red, white, and blue scarf. Walking among the other athletes, bumping shoulders with my teammates, I was bowled over by the sheer number of people present. Every athlete had worked so hard to be there, many overcoming obstacles we would never hear about. The pride, elation, and camaraderie are almost impossible to describe, and that marks the beginning of eight days of mind-blowing competition.

Katie Ledecky

The Ledecky FamilyMy race being so late in the swim schedule worked to my advantage in other ways as well. For one, I had time to adapt to the atmosphere of being in the Village and at the Olympics. The Village is an exceedingly cool place to be. It’s almost like a video game. You’re dodging Olympic-level speed walkers doing their training exercises with their hyperflexible knees. You’re strolling beside weightlifters and towering basketball players and demure gymnasts. All shapes and sizes of athlete, speaking in every language you’ve ever heard. Representatives from every country, mingling and chitchatting. Especially in the cafeteria.

We’re all hoping to get a glimpse of whomever is our own personal idol while we’re loading up our trays with grub. At the same time, you’re cheek by jowl with your competitors. The mix gives rise to a palpable buzz. It doesn’t feel tense so much as like you’re floating in this exclusive, singular bubble. There’s pin trading, like at Disney World. Everyone is over the moon to be there because we’ve all worked incredibly long and hard and consistently to earn a spot in the Village. When you’re there, among so many talented people, you feel like you’ve already won.

A second benefit of my late start time was I got to be a fan for the first five days of the Games. It gave me a chance to focus less on competition and more on the beauty of swimming at that level. No one is a bigger swimming dork than me. I attended every prelim and finals session. I got comfortable with the flow of the meet, observed how to walk out for races, learned little details about the run of show.

My year-round club swim team coach, Yuri Suguiyama came along to London too, but unfortunately, he wasn’t one of the official USA swimming coaches at the Olympics, and he wasn’t able to obtain a credential to come on the pool deck. I had kind of expected that he was going to be right there with me in the moments before the race, but because of regulations, he ended up stuck in the stands like any other fan attending the Games. I didn’t even get to connect with him before my prelim, which fell on day six of the games, the third of five heats that morning.

I remember my legs were shaking as I mounted the blocks for my first go, my nerves punching through. Despite that, I managed to win my heat, but I fell to third overall behind Lotte Friis of Denmark, and England’s Rebecca Adlington, who had taken gold in Beijing and was lauded as the hometown heroine of the games. Rebecca beat my time by more than two seconds.

To me, the only thing that mattered was that I had made it to the finals. My time of 8:23.84 was near what I’d done at the Trials, which boded well. Officials assign lanes by race times, fastest in the middle, slower on the outside. My time put me in the middle of the pool, in lane three.

I met Yuri outside the spectator entrance as soon as I could after my prelim. It was as if he was being kept behind the velvet ropes of a nightclub or something. I have this picture of the two of us meeting that one of my family members took. We’re huddled together whispering in the public area—among fans and competitors alike—about my stroke and my race strategy.

Despite the odd circumstances, Yuri was reassuring and focused. He emphasized how proud he was of me for making the final. I told him something along the lines of “I believe I can do it” and “I have nothing to lose.” Which was the truth. And that’s when he gave the last-minute advice that changed everything.

Yuri told me to breathe more to my right side and less to my left. In swimming, I’d been doing what’s called breathing bilaterally, which means you breathe to a mixture of your left side and your right side. Yuri didn’t say breathe only to the right. Just less. He wanted me to reduce the number of times I breathed left because he noticed that it was slower for me, and he wanted me to swim as fast as I could. That was his final technical instruction. Oh, and not to take the race out so hard and fast. To be more controlled. (This was not a new suggestion, but I appreciated the reinforcement.)

Last, as a warning, Yuri told me, “It’s going to be loud. You’re going to be in lane three. Rebecca is going to be in lane four. The place is going to erupt for her. I want you to get behind your block, and when it gets loud, channel all that energy down your lane. All that energy is for you. Don’t let it be more than that.”

Then he smiled and added, “You’re going to be great.”

After the prelims, I emailed a news story to my mom that read, “Rebecca Adlington Sets Up Nail-Biting Final in 800m Freestyle.” The story pitted Rebecca against Lotte. “It has always been us two,” declared Rebecca. As far as the press was concerned, I didn’t exist.

In reading the Olympic press, it became clear how big a race this was going to be. The Olympic Committee had scheduled the race toward the end of the night. It was advertised as two huge swimming giants, local sweetheart Rebecca and rising star Lotte, pitted against each other in lanes four and five. The two were viewed as rivals who had been in many prior tight battles and knew exactly how the other swam. I was nearly 100 percent certain neither Rebecca nor Lotte knew anything about my racing style.

The upside of the media’s hyper-focus on Rebecca and Lotte was that I could exist in the shadows with zero notice from the greater swim world. Being an underdog gave me space to concentrate on my own game. Invisibility would be my superpower.

Seeing Yuri had left me calmer than I’d felt in the prelim race. I knew I was ready, come what may. In a way, all these factors combined—my race time, my age, it being my first Olympic rodeo—enabled me to, if not relax, then feel zero pressure. No eyes were on me. No one was sweating me to deliver anything but my best effort. Not even my folks.

I called my mom the day of my race. She and my dad were concerned between themselves about what they would say to me if I flopped in my first ever international showing.

When I rang her, I said, “When I make the podium, even though your seats are really high, you’ll be able to move down for the medal ceremony.” My mom said, “Oh, great. That’s wonderful.” Then she hung up, turned to my dad, and winced.

“She thinks she’s going to make the podium,” she said. He answered, “Well, if she doesn’t, we will remind her that she’s just fifteen. And that this was a good experience.”

I smile, thinking about that conversation. And all the many other conversations when the topic was how to smooth over or assuage my devastation if I didn’t win a medal. No one in my family could conceive of my winning a medal at my first Olympics. My parents always get asked, “When did you know Katie was gonna make the Olympics?” And they shoot back honestly, “When she touched the wall at the Olympic Trials.”

To be clear, my parents were thrilled that I made it to the Games. But they were also realists, and they weren’t in the business of filling my head with fantasies they had no way of knowing could or would come to pass. They supported me from a place of love and consistency, which was separate from my accomplishments. If there is such a thing as the opposite of stage parents, my folks are it.

As for my own mindset, I consistently saw myself winning gold. At that point I think I’d only lost one 800 freestyle race in my life. I’d won the Olympic Trials. I’d won Junior Nationals. I’d won Sectionals. I had read that Michael Phelps’s coach, Bob Bowman, would have him visualize both the best-case and worst-case scenarios of every race. I tried to visualize different scenarios, but I struggled to visualize anything but winning. Given my record of success in the 800, I was convinced the odds were in my favor to win this race.

From my room in the Olympic Village, I sent an email to my parents that quietly shared that confidence. I reminded them again that if you win a medal, the family can come down to the swimmers-only section and throw flowers or take photos. My parents told me after the fact that when I wrote them this, they thought I’d lost my mind.

Before any race, I typically eat the same thing: plain pasta with olive oil and Parmesan cheese. In London, prior to my 800 free, it was no different. I wolfed down a plate of noodles at the Olympic Village before busing to the aquatic center early. By then the media coverage was at a fever pitch. Prince William and Princess Kate were going to be in the stands. As were Lebron James and a handful of other NBA players from Team USA Basketball.

I was in the pool warming up when my parents arrived. I waved to them, and one of the ushers noticed and asked who they knew swimming tonight. My mom said that their daughter was in the 800. The usher asked where they were seated, and my mom told her they were up in the nosebleeds, ten rows from the top of the arena. The usher explained that right before the 800, my folks should come down, and she would direct them to better seats.

My parents found their section, and my dad, ever practical, realized it might be impossible to find that same usher later. So they went back down, found her again, and volunteered to wait in the hallway until the 800, when she could retrieve them. The usher agreed to the plan, walked my parents to a side area, and said, “Wait here.”

The meet began, and of course, other ushers approached my parents, trying to discern why they were idling alone and not seated. This went on for several races, until right before my swim, when a new usher approached, pointed, and shouted, “You two!”

My parents freaked out. They were positive they’d be ejected from the arena and miss my race. Instead, they were walked to the best seats in the house, ten rows up, dead center, a perfect view.

When I walked in, Michael Phelps was there. Hood up and deep in thought, he was preparing to go out and swim the 100 fly, a race the media was reporting would be his last ever individual Olympic event. His mind must have been reeling with the significance of that milestone. The best in the world, headed toward what was meant to be his Olympic swan song.

As he passed by me, he gave me a high five and said, “Good luck, and have fun out there.”

For a moment, I was thrown back in time to when I was simply another young fan, clutching my swim cap, waiting in line for this swimming legend to acknowledge me and elated when he did. It was a small connection, but one that was so meaningful to a kid whose dreams were only just starting to coalesce. That fate would find us on the same team less than a decade later, and that he would again choose to take a moment to connect with me, says a lot about the family you build in the sport of swimming—and even more about the kind of person Michael Phelps is.

When I walked onto the London Aquatics Centre pool deck from the ready room, the crowd was riotous with collective anticipation for Rebecca. They were standing up to witness the coronation of their favorite swimmer. As the crowd screamed and shouted her name, I thought about what Yuri had told me—that the arena would be noisy, that the energy would be epic—and I told myself the chants of “Becky! Becky! Becky!” were actually “Ledecky! Ledecky! Ledecky!” I took a deep breath and assured myself that I would do what I had trained to do—take the lead and keep the lead. Attack and not look back.

Yuri, stuck watching me swim from just below the rafters, would later tell me I looked much more relaxed than I had in the prelims. He knew I’d listened to his counsel and stolen all that noise and enthusiasm to put into my own lane.

Typically, before the call comes to take your mark, I do three claps. That night, it was so noisy, I had some concern I would not hear the starter. I decided to forgo the three claps and bent into position and waited for my cue.

BEEEEEEEEP!

When I dove in, my mind was clear—blank, really. I was on autopilot. My coaches wanted me to swim a controlled first half of the race. I started so eagerly that I took the lead by the 50-meter mark. It was as if the adrenaline made my brain black out.

Just Add Water: My Swimming Life

$29.00, Amazon

I settled in my second 50 of the 800, and then my third 50 was faster than my second. Yuri recalled that’s when he was able to sit back and enjoy the race, because he knew it was going to be something special. Yes, I was going out fast, but I wasn’t spinning my wheels, I wasn’t out of control. I was pacing myself, not putting it all into the first 100 meters.

If you watch video of the live broadcasts of the race, the British announcers remained centered on Rebecca, mentioning me only to comment that I was foolishly going out too fast. Same for Dan Hicks and Rowdy Gaines at NBC. The coverage consensus was that as an inexperienced competitor, I was surging ahead, but would soon tire out.

After 150 meters, I broke away. By 200 meters, I’d flipped at under two minutes, faster than the world-record pace. Even in the water, the noise in the aquatic center was deafening. When I would turn my head to breathe, I was hammered by a wave of sound. It was the crowd, still chanting, “Becky! Becky! Becky!”

At the 600 turn, I had an epiphany. I thought, This is just a 200 free. I thought, I’ve done thousands of 200 freestyles in my life. I won’t mess this up. From that moment on, I felt vibrant, alive in my body, present. I registered every detail. The London Olympic signage. The crowd on their feet, waving pink and green “Becky” banners. The slosh of the water churning around me. I took a breath to the left, against Yuri’s orders. I couldn’t help myself. I had to see if anyone was sneaking up in lanes four, five, or six. They weren’t.

For the last 200, I was on my own. Well ahead of everyone else, in my first ever Olympics. The kid leaving everyone else in her wake. I felt like I was on another planet. For eight minutes, I swam like my life depended on it. Then I touched the wall.

Katie Ledecky

Clive Rose/Getty ImagesAnd just like that, I was an Olympic champion. I was the youngest athlete ever to have won the women’s 800 free at the Olympics. I’d beaten Rebecca by more than five seconds, breaking the U.S. record set twenty-three years earlier by Janet Evans. One of the broadcasters said, breathless and in disbelief, “We may have just seen the making of the new long-distance queen for the United States.”

Rebecca took third, losing to Spain’s Mireia Belmonte García. (A fact I did not register, honestly, until the medal ceremony, because I was so overwhelmed by the win.) My mom told me when she watched me race, she was so anxious that her mouth went dry. She didn’t know my competitors, the history of their races. While I was ahead, she didn’t trust that I could keep the lead. She assumed the other swimmers were holding back. But when I turned at the last 200, she, like me, knew I had it. She began jumping up and down. The usher who had been helping them came over, glanced at me in the pool, and gave my mom a giant hug. She still has a photo of the two of them on her iPad.

After I won, Rebecca was unbelievably gracious, far warmer than she had to be given the circumstances. The first thing she did was swim over and hug me, saying, “Well done, amazing.” She kept telling me how incredible I was, how she thought I could break her record, maybe even as soon as the next year. Even saying she was looking forward to watching me break it. It was clear all the prior pressure had fallen off her shoulders. I’m sure there must have been a level of disappointment, but she was a study in class. Her country should have been as proud of that as any swimming medal.

Rebecca Adlington and Katie Ledecky

Julien Behal/PA Images via Getty Images

Mireia Belmonte Garcia, Katie Ledecky, and Rebecca Adlington

Al Bello/Getty ImagesWhen I caught up with my parents and my brother, they were all kind of in a daze. Almost like shock. Like I said, none of my relatives expected me to win a medal. Never mind the gold. My mom’s uncle Red, who was eighty-six at the time, may have been the only true believer. He’d flown in from Washington state with his daughters. One afternoon he walked down to a little coffee shop near his Airbnb and started chatting with the locals there. He bragged that his grandniece was going to be swimming in the 800. They listened, offered good luck, but assured him I would never beat their Becky. Bullish, Red made the whole place a wager. If I won, he’d buy all of them breakfast. Apparently, he tried to make good on the bet the day after the race, but when Red went back to the restaurant, nobody was there.

While on the deck, I was handed a bouquet of flowers, which I threw to my brother to hold for me. In a strange twist of fate, our across-the-street neighbors in Bethesda, Dr. Kurt Newman and Alison Newman, had watched me swim from the second row. Ironically, they were the family who had originally recommended that my mom enroll us at the Palisades pool. None of us knew they’d be in London. While I was swimming my guts out, they were losing their minds, waving at my parents to join them near their seats. After the medal ceremony, they threw me an American flag. To this day, Kurt jokes that he wants his lucky flag back.

Next, Team USA took me to the International Broadcast Centre for press interviews. After the chaos of my upset, the media had a lot of questions.

“I don’t think two years ago I could ever have imagined this,” I said to a crowd of reporters circling me on the deck, noting it “was a great honor to be here” at all. I said that I’d known before I went out for the 800 that Michael had won that 100 fly and Missy the 200 backstroke. “Missy and Michael’s performances got me pumped up,” I told the gathered press. “I just wanted to see how well I could represent the U.S.”

When a reporter asked Michael Phelps about me, he said, “Katie went out and just laid it on the line. It looked like she went out and had fun and won a gold medal and just missed the world record. So, I could say that’s a pretty good first Olympics for a fifteen-year-old.”

Katie Ledecky at the TODAY Show

Warrick Page/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal/Getty ImagesEventually, I was reunited with my family and with Yuri. I don’t remember too much besides giving everyone a big hug. I’m sure there were some tears. I showed Yuri the gold medal. He had to leave the next day to coach a swim meet in Buffalo. It was a sectional-level meet with the other kids in my local group, and he’d missed the first two days, being in London to support me.

If you go back and watch my event, I breathe primarily to my right side, like Yuri suggested. But I do breathe a few times to my left, wanting to confirm that I’m still ahead. You can see as I take these covert breaths that I’m right on the world-record line. I ended up missing the world record by about half a second. I always think: Geez, if I had only listened to Yuri and breathed to my right side instead, maybe I would’ve broken the world record.

Though I didn’t get to spend too much time with Yuri in London, knowing he was there was profoundly meaningful to me. I wouldn’t have wanted him to miss that moment, the culmination of our efforts together. To be able to share that journey with him was crucial to me. I think both Yuri and I were able to embrace the experience and come away from it with a sense of belonging. We felt a sense of satisfaction, of a shared “mission accomplished.”

The family photos of that time show me wiping away tears on the medal stand, my fingernails painted red, white, and blue. There’s one photo I always think about. It’s a candid of me getting out of the pool after my prelim swim. My cousin snapped the picture, then posted it with the caption: “The last time Katie walked away from a race where she wasn’t an Olympic gold medalist.”

After I returned home to Bethesda, there were dozens of invites to events and appearances, like one to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at a Washington Nationals game. Ize’s deli, where I used to stop after swim practice, gave their tomato, cheese, and bacon omelet a new name: Katie’s Gold Medal Omelet. Even with all this excitement, I had school summer reading assignments to finish and an essay due on the first day of my sophomore year. It was quite the juxtaposition.

In September, I joined other Team USA members to visit the White House. Both President Obama and the First Lady spoke on the South Lawn. Mrs. Obama had been in London as the lead of the U.S. delegation, and she’d had a great Olympic experience, even getting lifted up by one of the women wrestlers in a moment that went viral. The president joked that he was jealous she’d gotten to see us compete in person, but he had followed the coverage from home.

Katie Ledecky and President Obama

Christy Bowe/ImageCatcher News Service/Corbis via Getty ImagesHe continued, “One of the great things about watching our Olympics is we are a portrait of what this country is all about, people from every walk of life, every background, every race, every faith. It sends a message to the world about what makes America special. It speaks to the character of this group, how you guys carried yourselves. And it’s even more impressive when you think about the obstacles that many of you have had to overcome not just to succeed at the Games but to get there in the first place.”

And then he mentioned me by name, a shock I still haven’t recovered from.

“Katie Ledecky may have been swimming in London, but she still had to finish the summer reading assignments for her high school English class.”

Everyone laughed. Then he searched the crowd to find me. “Where’s Katie? Yes, there she is.”

After pointing me out, then–Vice President Joe Biden came over to me and quipped, “I bet you finished that reading, didn’t you?” This was all heady stuff for a teenager entering her sophomore year of high school. Thankfully, my classmates and teachers did a great job of making things normal for me at school when I returned. I mean, sure, I did an assembly and answered a lot of questions about the Olympics. Students, teachers, everyone could ask whatever they wanted. But after that, the all-consuming feeling of having been a part of the world stage receded. At random times, I would feel somewhat overwhelmed, but I wasn’t exactly sure why.

I did my best to push forward and inhabit my school universe, until at one point during the winter of my sophomore year, I was hit with the recognition that although I kept telling people I felt my life was still the same as it had been, maybe it actually wasn’t.

Like it or not, I’d become a public figure. A professional athlete with an international audience. Being an Olympian, having that title and profile, was a massive adjustment. As was my brother leaving home and starting college. I was adapting to the fact that I was suddenly an only child in my house, and that my brother, Michael, the person who knew me best—and kept me levelheaded—was elsewhere. At school, it wasn’t as if I was treated as a different person post-London. But I kind of felt like one.

When I’d started at Stone Ridge the year before, I’d entered as a new freshman, not an Olympian; just another student trying to make friends. When I returned from London, Bob Walker, my spirited high school swim coach, counseled me that though I was a gold-medal winner now, my other qualities were what made me who I was. Bob, my classmates, teachers, and administrators helped me traverse the bridge between regular fifteen-year-old and Olympic gold medalist.

In swimming, it can be easy to get stuck in your own head. After all, you spend most of your time face down in the water, staring down at the black line at the bottom of the pool. Back at Stone Ridge, I was fortunate to be able to get back in the swing of things with my high school classmates on the swim team. We were all dedicated swimmers, but we also kept things fun and light. After London, I also took care to balance out my swimming with volunteering and committing to school service projects. I tried to maintain a connection to my community that went beyond the pool. By doing more, I filled my time, stayed occupied, literally spent more hours with my feet on the ground. I held on to who I always was while accepting who I was becoming. And I reminded myself every day that I was, like Coach Bob and Yuri and my parents so frequently said, so much more than a swimmer.

Excerpted from JUST ADD WATER: My Swimming Life. Copyright © 2024 by Katie Ledecky. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Originally Appeared on SELF

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports