Dad's the main advisor in department of Justice

Over the years, father and son have shared many heart-to-heart conversations about hockey. They have discussed the commitment, hard work, discipline and long hours necessary to make it to the next level.

Now, with his son old enough, the father imparted his wisdom on a subject he was all too familiar with: fighting.

As a former pro hockey player, Rocky Dundas had seen his share of fisticuffs. So, when the Toronto Maple Leafs made it clear that if he wanted to stay in the NHL it would be as a full-time enforcer, Dundas was forced to make a tough decision.

Despite having two years left on his contract, he quit pro hockey for good.

“I didn’t want to do that anymore,” said Dundas, who left the NHL after playing five games with the Leafs during the 1989-90 season. “I still had a couple of years left on my contract, but I had an internal choice to make. It was an easy choice in the sense that I didn’t want to fight any more.”

On a recent Sunday afternoon in Brampton, Dundas watched intently as his son, Justice, a forward with the Ontario Hockey League’s Sarnia Sting, dropped the gloves with Battalion defenceman Zach Bell. The pair traded punches with fists connecting on both visor and face before being separated.

So how does the elder Dundas feel about seeing his baby boy fight?

“It’s an interesting dynamic,” said Rocky Dundas. “I sat down with my son and said, ‘You have a choice to make and that is to find your role and your niche. You’ve got to make a conscious decision to be right with it internally.’ As a parent, there’s always a concern. What he chose to do and how he defined his role ... when he moved into junior he had to turn in that direction. And when he made that choice, I had spent my time walking him through the impacts of that.”

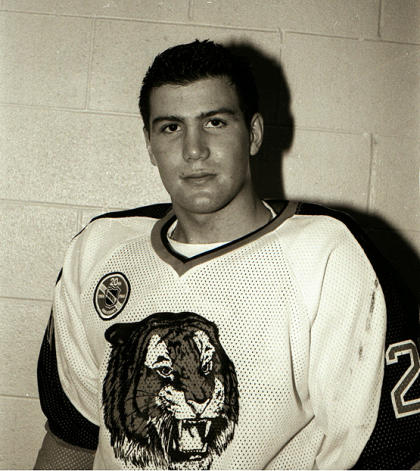

Justice Dundas is definitely not your prototypical enforcer. He’s not afraid to fight, but it’s far from the only tool in his arsenal. Last season, he had three points and 16 fighting majors in 44 games. This season he already has five points and two fights in 15 games and has spent time on Sarnia’s top line alongside Montreal Canadiens first-rounder Alex Galchenyuk.

“It’s different for me because it’s not like I have to fight,” said the younger Dundas. “I want to stick up for my teammates and I want to protect guys on my team because that’s my personality. I’m very protective of my friends and family, so it correlates on the ice and I have no issues doing that at all.”

During his own junior career in the Western Hockey League, Rocky Dundas was anything but a goon. He was a skilled player with true grit. In his best season, he scored 31 goals and 70 assists in 71 games with the Spokane Chiefs in 1985-86. The following year, after a trade to Medicine Hat where he joined future NHLers Trevor Linden, Dean Chynoweth, Rob DiMaio, Wayne McBean and Mark Fitzpatrick, Dundas contributed more than a point per game to help the Tigers win a Memorial Cup championship. He was selected by the Montreal Canadiens in the third round (47th overall) in the 1985 NHL entry draft. It wasn’t until he began playing pro that his role started to shift.

“I went to Montreal and I had 100 points (in junior), but I was playing with guys who had a 160 points and 180 points,” said Rocky. “You realize that there’s a directional change and that’s what I was asked to do. You realize that there are certain roles and because I fought a little bit and played a little more aggressive, that was a far easier transition.”

The younger Dundas chuckles when asked about his dad’s scoring prowess in junior.

“He had a couple more points than I’ve had, that’s for sure,” said Justice. “We chirp each other about that.

“He had a couple of tussles back in his day, too,” added the 6-foot-2, 199-pound winger. “I think I’m a bit better of a fighter than he was. Maybe I should be giving him more advice than he gives me. But he just sat me down and taught me about things to do, ways to win, and to protect myself. It’s dangerous, especially going against guys – with my size – going against guys that are three or four inches taller and have a few more pounds on me.”

Like any parent, Rocky said his primary concern is to make sure Justice is safe. As someone with some experience in the field, he’s had a number of talks with Justice about fighting. He has shared his thoughts on the mental and emotional components, which are rarely understood by those who have never had to fight for a living.

“I wanted to talk to him first about protecting himself and second about the attitude towards fighting,” said Rocky. “Not many people have the capacity to look another man in the eye and drop the gloves in an arena full of 20,000 people, and there’s no one else to save you. What that means and what that’s like – the energy and the fear.

“I want him to be prepared for that endeavour, to know what the emotional implications are: What happens if you get injured? What happens if someone else gets injured? Those kinds of things are extremely important to discuss. His safety and the safety of others is very important.”

In May, when Justice celebrated his 18th birthday, his present was two tickets to watch the Predators in Nashville and a visit to see his “Uncle Stu” – better known as former NHL enforcer Stu Grimson. It was there that Rocky asked his longtime friend to talk to Justice about the rigours of playing that role for a living. Grimson amassed more than 2,000 penalties in minutes and more than 200 fighting majors over a span of 15 seasons. Rocky felt that Grimson, now a lawyer, would provide a different perspective from his own and that perspective would be valuable for Justice to hear.

“He knows what it takes and he knows what comes along with it psychologically,” said the Richmond Hill, Ont., native. “We talked about the burdens you can have from it, too. He explained what it takes and he told me that if I was prepared to do it, it’s a tough way to live.”

Justice said he understands why fighting forced his dad to walk away from the game he loved, especially in the wake of the sudden deaths of prominent NHL enforcers Rick Rypien, Wade Belak and Derek Boogaard.

“I understand 100 percent,” said Justice. “You’ve seen it in the past couple years with the suicides and what not, and people passing away because of the effects and the stress related to it. I can completely understand what (my dad) went through and why he pulled away.”

After his hockey career was over, Rocky went on to get a Master’s degree in adolescent education and worked as a youth pastor for 13 years. He and wife, Janice – a professor at Humber College – raised three children: Kasia, a journalism student at Ryerson; Bronte, a member of Canada’s junior national trampoline team; and Justice.

Rocky has no regrets about the decision he made more than 20 years ago. He said he’s glad he left pro hockey when he did given all the new data surrounding the lasting effects of concussions. He is thankful there’s more awareness of head injuries now that Justice is playing.

“I was fortunate that I eliminated some of the potential threat of that with a career change,” said Rocky, now the national retail sales manager at Trimark Sportswear. “So, I am grateful.”

Justice is grateful, too, for the guidance, love and support he’s received from his dad in helping him navigate his way through what can, at times, be a tough game.

“We’re really close so we’re open to talk about anything,” said Justice. “He's helped me a ton.

“He’s been the most influential person in my life.”

Sunaya Sapurji is the Junior Hockey Editor at Yahoo! Sports.

Email: sunaya@yahoo-inc.com | Twitter @Sunayas

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports