Star Power: Be they ever so humble, recruiting rankings still do the job

With signing day looming, it's time for the Doc's annual, week-long examination of the recruiting-industrial complex. Part One: The basics: Correlating recruiting rankings and success.

The holy hour of the vast, seedy recruiting underworld, national signing day, is a little over a week away, which is also the signal for legions of recruiting skeptics to sound their annual, anecdotal chants of "Ryan Perrilloux!" and "Notre Dame!" and snake oil!" A lot of coaches who live and die on the recruiting trail will tell you the recruiting rankings are a lot of bunk. Occasionally, they make a persuasive case.

Which is why, once a year, I make it a point to get back to the basic premise: Beyond the vagaries, the hype and the busts, the recruiting rankings still represent the most reliable system at our disposal for making initial assumptions about teams and players alike. The most important assumption being, as always, that recruiting is still the No. 1 predictor of success.

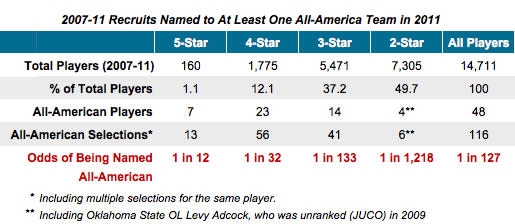

Individual rankings. On All-Americans, for example: If you were to go back and review the projections for the 47 players named to one of the five All-America teams officially recognized by the NCAA — American Football Coaches' Association, the Associated Press, the Football Writers of America, the Sporting News and the Walter Camp Foundation — in 2011, only seven came into college as can't-miss, five-star blue chips, the cream of the crop.

By contrast, more than twice as many of those All-Americans — 18, to be exact, more than a third of the total —were rated three stars or lower by the recruiting services. According to the gurus, the top three or four recruiting powers in the country should field more talented rosters than that by themselves, right?

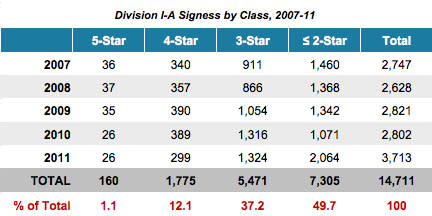

Right, if your standard involves zero margin for error, in which case you may as well stop reading. Fortunately, because we've been bestowed by the American education system with the magic of basic arithmetic, we do know better. If you look more closely at the relationship between initial expectations and eventual production, there's a very good reason for the heavy distribution of lower-ranked players among the nation's best, beginning with the distribution of stars at the beginning of the process, according to Rivals' extensive database of signees to I-A schools over the last five years:

I would hope that two and three-star players could acquit themselves well enough to produce a large number of big names, since they account for more than 85 percent of signees nationally. Again, using the rosters of the five NCAA-recognized All-America teams, the situation changes dramatically when you look at the All-America numbers in light of those ratios:

Maybe a raw ratio of 1 in 12 — or even 1 in 10, or whatever the "adjusted" number is after accounting for the early departures, injuries and academics that these numbers make no attempt to reflect — isn't all that impressive by itself. After all, that means far more elite recruits are falling short of their star-studded birthright than are reaching it. Across the board, failure and mediocrity are the norm, but if you think of a four or five-star player as a guy who is supposed to become an All-American — and a two or three-star guy as someone who is definitely not supposed to become an All-American — then yes, the rankings frequently miss.

On the other hand, if you consider the initial grade as a kind of investment — a projection of the how likely a player is of becoming an elite contributor compared to rest of the field — well, you'd put your money with the "experts" over the chances of finding the proverbial diamond in the rough every time:

Of course, a large number of players in that sample size haven't finished their careers, but you can divide up the numbers over any time period you'd like — one year, five years, 10 years: The ratio always looks identical on a per-capita basis, and it is not a crapshoot. Four and five-star players are roughly seven times as likely as two and three-star players to land on an All-America team, and the numbers in the NFL Draft tend to be even more lopsided toward the hyped recruits. All the more reason to want as many of them as you can get your hands on.

Fine, but for the skeptics, maybe still a little narrow. If you play to win the game, shouldn't the validity of recruiting rankings hinge on, you know, wins?

Obviously. So let's look at the records.

Team rankings. To do that, we have to start by identifying exactly — more or less — what the rankings project for each team. Using the "star" scale in a slightly different capacity, I classified all 65 teams in one of the "Big Six" conferences (the ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-10 and SEC) along with Notre Dame, BYU and TCU into one of five "classes," based on each team's accumulated recruiting rankings over the last four years.

The designations are based strictly on the combined scores of the rankings alone, with no attempt to account for injuries, transfers, academic casualties, arrests or any other routine form of attrition:

'Big Six' Conference Teams by Recruiting Class*

• Five-Star: Alabama, USC, Florida, Texas, LSU, Florida State, Georgia, Ohio State, Oklahoma.

• Four-Star: Notre Dame, Auburn, Michigan, Tennessee, Clemson, Miami, UCLA, Oregon, South Carolina, North Carolina.

• Three-Star: Ole Miss, Texas A&M, California, Nebraska, Virginia Tech, Penn State, Stanford, Arkansas, Oklahoma State, Michigan State, Washington, Missouri, Texas Tech, Arizona State.

• Two-Star: Maryland, West Virginia, Mississippi State, Pittsburgh, Minnesota, Illinois, Kansas, N.C. State, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Rutgers, Virginia, TCU, Boston College, Wisconsin, Iowa, Georgia Tech.

• One-Star: Louisville, South Florida, Kansas State, Kentucky, Baylor, BYU, Oregon State, Iowa State, Cincinnati, Washington State, Vanderbilt, Purdue, Syracuse, Northwestern, Duke, Wake Forest, Indiana, Connecticut.

- - -

* Based on Rivals' accumulated rankings, 2008-11.

To judge their success with respect to strength of schedule, I avoided catchall, potentially apples-and-oranges numbers like straight winning percentage, and limited the look to the major conferences both to keep the research manageable and because the rankings tend to be virtually indistinguishable in the mid-major conferences, where the vast majority of players are obscure two-star types who may not have appeared on the recruiting gurus' radars at all. Impressive success of Boise State and TCU notwithstanding, it's safe to say the smaller conferences' grisly track record against the "Big Six" speaks for itself.

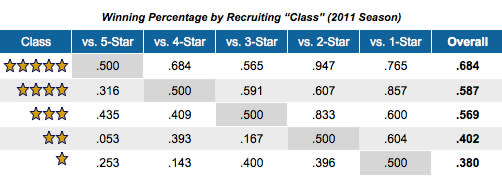

Instead, I looked at each of the 343 games over the course of the 2011 season between two major conference teams, and logged the results according to the recruiting "classes" outlined above:

2011 was not a banner year for the usual suspects — Ohio State turned in a losing record for the first time in well over a decade; Florida and Texas barely struggled past .500 — and a great one for middle-of-the-pack recruiters like Arkansas, Michigan State, Oklahoma State, Stanford and Wisconsin. Still, on the final count, the higher-ranked team according to the recruiting rankings won more than two-thirds of the time (68.7 percent of the time, to be exact), and every "class" as a whole had a winning record against every class ranked below it. The gap on the field also widened with the gap in the recruiting scores: At the extremes, "one-star" and "two-star" recruiting teams managed just five wins over "five-star" recruiters — four of them coming at the expense of Florida State and Texas — in 31 tries.

It's a simple equation: The better your recruiting rankings by the gurus, the better your chances of winning games, against all classes. Emphasis on the word chances — the counterexamples are obvious and legion in both directions. But as far as forming a reasonable basis for predictions, well, it probably goes without saying that you never want to count on being one of the anomalies.

- - -

Matt Hinton is on Facebook and Twitter: Follow him @DrSaturday.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports