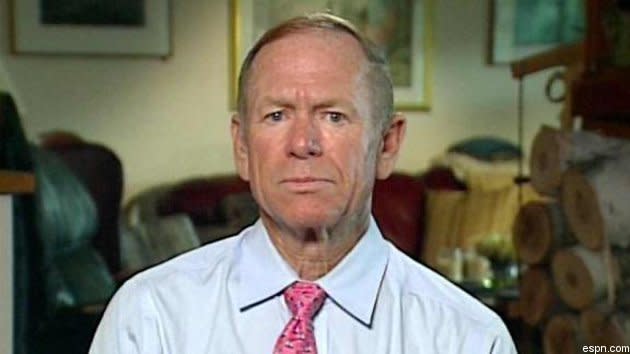

Interview: Dr. Robert Cantu on where concussion research is at the end of 2012

Concussions were a dominant CFL story in 2012, but they're also an issue that's going to be a huge focus for all levels of football going forward. Earlier this month, I spoke with Dr. Robert Cantu, one of the most prominent concussion researchers out there. Dr. Cantu is a founder and co-director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE) at Boston University, and he's also a co-author (with journalist Mark Hyman) of the recently-released book "Concussions And Our Kids". Here's what he had to say about why he wrote that book, where concussion research is at right now and what it means for football in both Canada and the U.S. going forward.

For Dr. Robert Cantu, the key to changing how leagues, teams and individuals approach concussions isn't medical associations delivering bans on certain sports. Rather, it's education on the potential impact of concussions, which will then allow people to have all the information before they have to decide what to do.

"The doctors can talk about it all they want, they can ban things, but nobody's going to listen," he said. "I'm just trying to give them information to make an informed decision."

He said the potential consequences for kids in particular motivated him to write his book.

"Youth brains are particularly more vulnerable than adult brains," he said. "They are damaging their brains or risking damage to their brains that can dramatically alter their future lives. It can alter the whole trajectory of a life."

Cantu said a particular incident that compelled him to focus on concussions and how they relate to kids came when he and a group of other doctors went to USA Football about two years ago with a recommendation that flag football programs for younger kids should be expanded to minimize head trauma at younger ages. They were told "The parents won't sign the kids up for flag football." (Note: See * update at end.)

"It just kind of got me so mad, I made the decision I've got to write this book," Cantu said.

The book's full of plenty of information on how concussions affect athletes at every level, but one of the most notable passages is on athletes' attempts to "beat" concussion tests by purposely scoring lower than they normally would on the baseline examinations given at the start of a season. Cantu said some athletes do that so that they can still appear all right after they've been concussed.

"Athletes all the time now, they understand what that test's being used for, so they do what we call sandbagging," he said.

As we've seen in the CFL time and time again, concussion tests aren't perfect and some questions still linger after an athlete passes them. That may be perfectly innocent, but the idea of sandbagging can't be dismissed. Cantu said there's no perfect way to beat the impulse to sandbag, but education on the dangers of concussions has to increase so that players realize the risks of lying and playing through concussions. He added that team doctors should keep an eye out for players who perform worse than what would be expected on a baseline test.

Some notable recent research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) suggests that it's not just diagnosed concussions that are problematic. Cantu said fMRI research has shown cognitive declines even in football players who haven't suffered a concussion over a season, much of which is likely from subconcussive trauma.

"Over the course of a football season, there's significant deterioration in a number of players," Cantu said. "It certainly suggests individuals should be tested over the course of a season."

Cantu said that research demonstrates how even head hits that don't cause a diagnosed concussion are troublesome.

"Those subconcussive blows are not necessarily innocuous," he said. "The strong point in those cases is that some players have never been diagnosed with concussions."

Cantu said that suggests tests should be done more frequently than just in the preseason or when someone has concussion symptoms.

"There should be tests that are done not just preseason, but midseason and end of season, and not just in symptomatic individuals," he said.

He added that just because an individual passes a concussion test also doesn't mean they're okay, as many symptoms can be delayed. That was seen in the CFL this September, when Winnipeg quarterback Buck Pierce passed an initial concussion test and returned to the game, but later developed concussion symptoms and came out.

"We also do know that concussion symptoms can occur in a delayed manner," Cantu said. "That's probably part of the reason for the great disconnect between recorded concussions on the playing field and symptoms players complain of."

Not all of that is necessarily innocent, though, and part of the reason is that football players have substantial incentive to try and play though injuries. If they don't, they can lose their jobs. That happened with San Francisco 49ers quarterback Alex Smith this year, who was concussed and lost his starting role to Colin Kaepernick while he was recovering. Cantu said the team's handling of that situation might convince some players to lie and say they're not experiencing concussion symptoms for fear of losing their jobs.

"That was very unfortunate how that played out," he said. "It definitely reinforced the concerns."

Cantu said the high turnover rate and non-guaranteed contracts at most levels of professional football present their own challenges, as players are always worried about being replaced.

"The terrible thing about football is that most of the players have non-guaranteed contracts," he said. "You're constantly looking over your shoulder."

If Cantu could change one thing about football, he said it would be the amount of hitting in practices, which can add up over a season. He said even hitting once a week in practices and once a week in games is still a substantial amount of head trauma, whether concussive or subconcussive.

Cantu's Boston University group's research is mostly focused on former NCAA and NFL players, but they've looked at some CFL players as well, and found CTE in the brain of former Winnipeg Blue Bomber Doug McIver. He said concussions are a huge issue north of the border as well, but the differences in the CFL game (specifically the bigger field and the emphasis on passing) may help reduce the prevalence of concussion-causing hits.

"It's not that the hits aren't as hard, it's that there aren't as many of them," Cantu said.

Some impressive concussion research is being done north of the border as well, particularly by Dr. Charles Tator's Canadian Sports Concussion Project (which found CTE in the brains of former CFL players Jay Roberts and Bobby Kuntz). Cantu said he has a huge amount of respect for what Tator's accomplished with that project and with his ThinkFirst education initiative, and he's happy to see other respected doctors investigating CTE.

"He's done marvelous work in ThinkFirst," Cantu said. "I'm thrilled they're involved with CTE research."

Cantu's optimistic that the work of Tator and others will lead to greater focus on concussions in Canada, as the issue is just as important north of the border.

"The brain doesn't know whether it got concussed in Canada or in the U.S."

*Update: USA Football's Steve Alic offered the following comment on the aforementioned 2010 meeting:

Scott Hallenbeck, USA Football’s executive director, hosted Dr. Cantu at our office in Feb. 2010 – their meeting involved no other doctors. In terms of flag football, USA Football manages and operates one of America’s most popular youth flag football programs with approximately 200,000 players nationwide. Conversely, we do not run tackle football leagues. We offer coaching education with a strong emphasis on player safety – including concussion awareness – for coaches in both youth flag and tackle football. Our resources and best practices are adopted by youth leagues nationwide.

We do not have the ability to mandate our resources, such as coaching education, but leagues value and employ what we put forth. Our members – youth football coaches, players, parents, commissioners and game officials – reside in all 50 states. You can see more at www.usafootball.com.

During Dr. Cantu’s visit, when discussing flag football and tackle football, his paraphrasing misses the mark. Our executive director informed him that parents seek a safer way to learn and play tackle football, which is what we’ve done and continue to do with some of the world’s leading doctors in concussion research and treatment. Again, we do operate flag football leagues.

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports