Marvin Miller paved way for Scott Boras' success

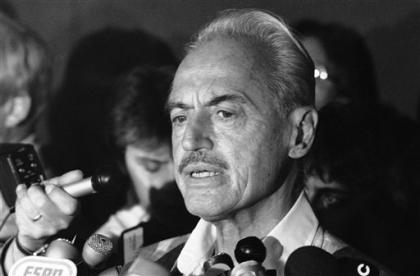

On a blustery March afternoon on East 57th Street in New York City, a black town car steered to the curb at the Four Seasons hotel. Marvin Miller, dressed in an olive sport coat over a crisp white shirt, hoisted himself from the rear passenger seat. Scott Boras crossed the sidewalk to greet Miller, who was six weeks from his 95th birthday and traveling alone.

Admittedly in failing health but holding himself as tall as he could, Miller bypassed the bank of elevators and insisted on navigating a flight of stairs. Boras took each step with him, a sheet of notebook paper folded into his jacket pocket. In preparation for their lunch, Boras had written some 20 questions.

They'd met twice in passing over the previous three decades. Here, for the first and last time, they'd come together for soup and conversation. On one side of the table, the baseball establishment's villain in the era of player unification and bloody labor wars, of Curt Flood and the stricken reserve clause. On the other, its villain at a time of escalating player salaries and rights for drafted players, of Alex Rodriguez and the age of information.

Boras hoped for an hour, maybe two. Miller gave him five. Throughout, Boras would ask Miller if he was OK to continue, if he was up to it, and each time Miller would smile and nod. "Yes," he'd say, and his eyes would fire again as he launched into a story about Bowie Kuhn or Mickey Mantle or one exasperated owner or another.

"I walked on his stage," Boras said Wednesday evening, seven months later and not long after learning of Miller's passing. "And I realized where my wings came from."

[Also: 'Steroid Era' athletes headline Baseball HOF ballot]

He'd requested the meeting out of curiosity and what he knew could be a last chance to sit with the man who'd furthered the game, back when the battles were raw and seemingly unwinnable. Boras had skimmed in that wake and then carved his own. To stand with players often was perceived as standing in the way of the game, not with it. Over 16 years, from 1966 to 1982, the Major League Baseball Players Assn. advanced from a backroom notion to the strongest union in professional sports. It required strong men, players with unbending consciences and skin as thick as horsehide. And it required a leader.

Thirty years in the business, Boras wished to introduce himself to that man. He wished to hear the stories, understand the burdens and feel the passion for them. He also wished to thank Marvin Miller. So he sent a town car, which delivered a frail and failing Miller, once among the most powerful voices in the game. A photo of the two of them from that afternoon hangs in Boras' office.

"He was amazing," Boras said. "It was kind of like Disneyland for me."

Miller recounted his meetings with Flood and their fight against the reserve clause, abolished in 1975. Free agency followed. He recalled bumping into Kuhn, then the commissioner, on a street in New York, and how that conversation brought about the appointment of an impartial arbitrator for the hearing of grievances. How Mantle, nearing the end of his career, had graciously offered to step aside for the advancement of a pension plan. And the hand-to-hand combat of negotiations. Always, it seemed, the negotiations.

Hardened, of course, by his work with the United Steelworkers union, Miller was a relentless advocate for the men on the job, whether they forged railroad lines or rolled singles through the middle. The union was the mortar, he told Boras, that held the bricks of the industry in place, and that maintained balance within the industry.

None of that made Miller particularly popular outside the players' union, but this was the cost of the vision, of the job. And of the balance.

"Marvin talked a lot about that," Boras said. "He made a reference to the idea that you're for the players and more importantly for the game. You're part of the balance of the game, a weight on the scale. In the end, focus on the balance. It could never be the weight that is attached to you. Focus not on achieving the medium, the fairness, the standard of relationship, the quid pro quo. The focus for you is in the moving, the grind. With that, you wear the horns of the negotiations."

This is what Boras has come to know. If not on the scale of Miller, who led an entire industry, then on a player at a time. The most arduous work was done by the time Boras arrived in the early '80s. But, their work – Miller's, then Boras' – often was cast similarly, that of greed over the game, of the individual over the institution. They stood before microphones and delivered the bad news. They held out for more. They fought the best they could and were accused of far, far worse.

[Also: Nolan Ryan to release beef cookbook in 2014]

Years later, Boras saw in Miller's eyes the satisfaction that comes from a sturdy game, one he helped create. He saw regret in what it may have cost him – his health and, at times, his family.

"This is hard for most," Miller told him. "The reason is, only time will measure you. If you believe that, others will never measure you."

Said Boras: "That, to me, that's Marvin Miller. The others of the moment vilified him. Time measured him completely different. By all."

When Miller passed, the stories were of a life well spent. What followed were pleas to make room for him in the Hall of Fame. Perhaps that would have been important to Miller. Perhaps not. To the people still riding his wake, his inclusion would only seem just. His story would seem worth telling, and retelling.

For a day, Boras was the audience of one.

"It was like going to a theater and having someone explain the evolutionary history of labor in Major League Baseball," he said. "Marvin was the voice of Orson Welles. It was beautiful.

"This is the largest thread of the fabric of baseball in the last half-century. You could not exclude Marvin Miller from the Hall of Fame. It's wholly unethical to be on those committees and let personal bias get in the way of the history of the game."

After five hours at the Four Seasons, Miller insisted again on taking the stairs. "Bear with me," he asked, and the two slowly made their way to the waiting car. It was then that Boras realized he'd never taken the questions he'd prepared from his pocket. The afternoon had gone too quickly. Two months later, he called Miller to say hello and ask how he was.

Miller chuckled.

"I'm not doing well," he said. "But I feel well."

Fantasy advice from the Yahoo! Sports Fantasy Minute:

Other popular content on the Yahoo! network:

• NFL players use Viagara to boost on-field performance, says Bears' Brandon Marshall

• Pat Forde: Louisville's move to ACC a sporting miracle

• 'Happily married' Hope Solo stands by Jerramy Stevens, who is back in jail

• Y! News blog: Scientist claims to have sequenced 'Bigfoot' DNA

Yahoo Sports

Yahoo Sports